30 December 1941. Rangoon, Burma.

allanpcameron

Donor

30 December 1941. Rangoon, Burma.

The men of 20th Indian Brigade marched out of the port and onto a train to take them to Pegu where 10th Indian Division was being concentrated. The men had been brought to Burma onboard RMS Queen Mary, along with the Division’s artillerymen, engineers and the rest of the men that made up a Division’s fighting ability. The men of 21st and 25th Brigades had sailed on RMS Queen Elizabeth. The two troopships normally ploughed the sea between Australia and the Gulf of Aden. The need to bring the 10th Indian Division to Burma as speedily as possible had meant a detour to Basra. Standing off Rangoon because of the threat of air attack, the men had been transhipped onto other smaller vessels to carry on into the port. General Auchinleck had to fight tooth and nail for the 10th Division to be sent to Burma. With the fighting in Malaya, Percival had been hoping for this Indian Division on top of the recently arrived Australian 9 Division and British 18th Division. General Alexander, newly appointed as GOC Burma Army, had won the argument with the War Office that this Division was crucial to his plan to hold Burma. This, along with Auchinleck’s interventions, had been accepted.

Some of the ships normally used in the Mediterranean between Alexandria and Tobruk and in the Red Sea between Port Sudan and the Suez Canal had been sent to pick up 10th Division’s equipment. These ships, with various escorts, were already in the Bay of Bengal and expected to arrive within the week. Among the equipment was 252nd Indian Armoured Brigade’s mix of light tanks, some well-travelled Vickers A9s and A10s, armoured cars, and 14th/20th King's Hussars’ had M3 Stuart tanks.

Major-General Bill Slim and some of his staff had been in Rangoon for a week trying to sort out all the practicalities of moving and training a Division from one theatre to another. Major-General Arthur Wakely’s 7th Indian Division already had two of its Brigades in Burma. The 13th Brigade had been under the command of the Burma Division. The 16th Brigade was finally complete with all three Battalions concentrated at Mandalay. With the arrival of 14th Brigade, and the Divisional Troops, Wakely, like Slim was trying to get his Division sorted out. The arrival of General Harold Alexander was expected within a day or two. He was currently in Calcutta with General Auchinleck being briefed on the situation, especially about the need to work with the Chinese to keep the Burma Road open.

The other problem that Slim had to deal with was the likelihood that he would be promoted to Lieutenant-General and be put in charge of a newly formed Burma Corps. Slim had requested that General Auchinleck appoint Brigadier Douglas Gracey from 17th Indian Brigade in Iraq to take over as GOC 10th Indian Division. Slim was also aware that a Corps would need a lot more staff that were currently on hand. Auchinleck had negotiated with Wavell to give Alexander help with staff, on top of what he could spare himself from India. Slim had been promised that he would have a proportion of those staff officers when they arrived.

In the meantime, Slim and Wakely had visited Major-General Charles Fowkes (GOC 11th African Division) whose HQ was near Moulmein. They also met with Major-General James Scott (GOC 1st Burma Division). Losing 13th Indian Brigade, Scott was now facing the question about how his two remaining Burmese Brigades would be used. Without Harold Alexander’s input, Slim wasn’t able to say for definite. He admitted that frankly he would like Scott’s men to spend some more time training, both themselves and especially training new arrivals in getting to know, and not fear, the Burmese jungle. Slim was also aware that both Wakely and his men would need translators and local guides. Having some of the Burma Rifles or police on hand would prove very useful.

In discussions among the generals, it became clear to Slim that native Burmans made up a very small percentage of the Burmese forces. Scott noted that his forces (army, police, frontier, auxiliaries, territorials) had over 27000 men, but of that less than 4000 were Burmans. The largest contingent were Indians (over 10000), with substantial numbers of Karens, Chins and Kachins (just under 10000). Scott confirmed what Slim had already been advised by Lieutenant-General Donald McLeod, outgoing GOC (Burma Army), that the political temperature between the various nationalities within Burma was rising. There was a strong independence movement amongst the Burmans, influenced by Gandhi’s Congress Party in India. McLeod’s police had evidence that this was being supported and promoted by the Japanese. There was a real fear that this movement would work at undermining the defence of the country, especially in providing the Japanese with translators and guides. It was even possible that there would be a threat from fifth column activities. All of this made Slim and Wakely keen to enlist Scott’s help to procure reliable locals to support the two Indian formations.

Slim and Wakely were then informed of the existence of the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo officially known as Mission 204 or ‘Tulip Force’. This had been founded to train Australian and British troops in guerrilla warfare for the British Military Mission to China. The secrecy surrounding it came from the time when support for the Chinese was kept as hidden as possible so that there would be no justification for a Japanese attack on the British Empire. Major Michael Calvert was forming his trainees into three Special Service Detachments, or Commandoes. These were all small forces, but available to Slim and Alexander. Calvert was keen on using these commandoes as the Long Range Desert Group had been used in North Africa. The use of irregular troops in the East African campaign had played an interesting role, especially Gideon Force, not one that Slim was terribly keen on, but open to.

Slim was also introduced to the existence of the Oriental Mission, which had been founded in Singapore in May 1941 as the regional headquarters of the Ministry of Economic Warfare. Force 136, as it was known, was designed to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in British territories that might be occupied by an enemy. Slim was informed that they were supporting Lt Col Noel Stevenson who had begun to organise levies from amongst the Karen tribesmen in the Shan States. Stevenson had served with the Burma Frontier Service and had extensive experience of working with the Karens. There was little time, few resources and next to no equipment, but many Karens were being organised to keep watch on Japanese movements and to identify Burmese collaborators. These two pieces of information made Slim realise why General Alexander had asked for Brigadier Orde Wingate to be attached to Burma Command.

Slim noted that having some kind of intelligence gathering system would be crucial and made a note to speak to Alexander about setting up some kind of organisation to provide his Corps with timely and accurate information about Japanese activities and intentions.

As he was new to the area, Slim had paid particular attention to the fact that there was a very limited road network and the railway ran north to south rather than east to west. Slim knew the 11th African Division from East Africa and noted their lower-than-normal establishment of motor vehicles. This was a double-edged issue. On one side, they weren’t tied to the roads so much. On the other side, their movement would be generally slower than a Division with the full allocation of Motor Transport. Slim was interested in how both the Burma Brigades, and the Africans were using more in the way of mules for resupply. Looking at the country, he could see the logic of having ‘all-terrain’ means of getting ammunition, water and rations to units.

The logistics of supporting a force in the east of Burma were going to be difficult. The vast rivers that flowed north to south were useful barriers against an invasion, but the limited bridges and ferries hampered supplying the defenders. There was an obvious danger of traffic jams along the limited roads waiting to cross rivers. This would be an invitation to the Japanese bombers to do great damage with little effort. Slim and Wakely would have to sit down with their staffs and work out how best to make sure the men had adequate supplies at all times.

When the problems had begun in Iraq earlier in the year, the initial forces had been flown into Basra by RAF transports. Slim knew very well the importance of air support, not only in defending troops against the enemy’s bombers, and in attacking the enemy’s troops, but also in re-supplying forces in emergencies. The RAF’s weakness in Burma was a real concern, one that needed more bombers, fighters and transport aircraft. This was out of Slim’s hands, but again something to discuss with Alexander when he arrived.

Something else that would need to be discussed was the threat of malaria and other diseases that would hamper the fighting power of the Indian troops. Slim had been informed by Brigadier Eric Lang, (Director of Medical Services) about the struggles to increase the levels of medical support for the growing army in Burma. Slim knew very well that the health of the troops, keeping the men fit and healthy, would have massive benefits, as would keeping up their morale. While getting more men and equipment was always going to be important, looking after the men and equipment already present was just as important. Until such time as all the reinforcements arrived, Slim had to take as much care for the men under his command as possible.

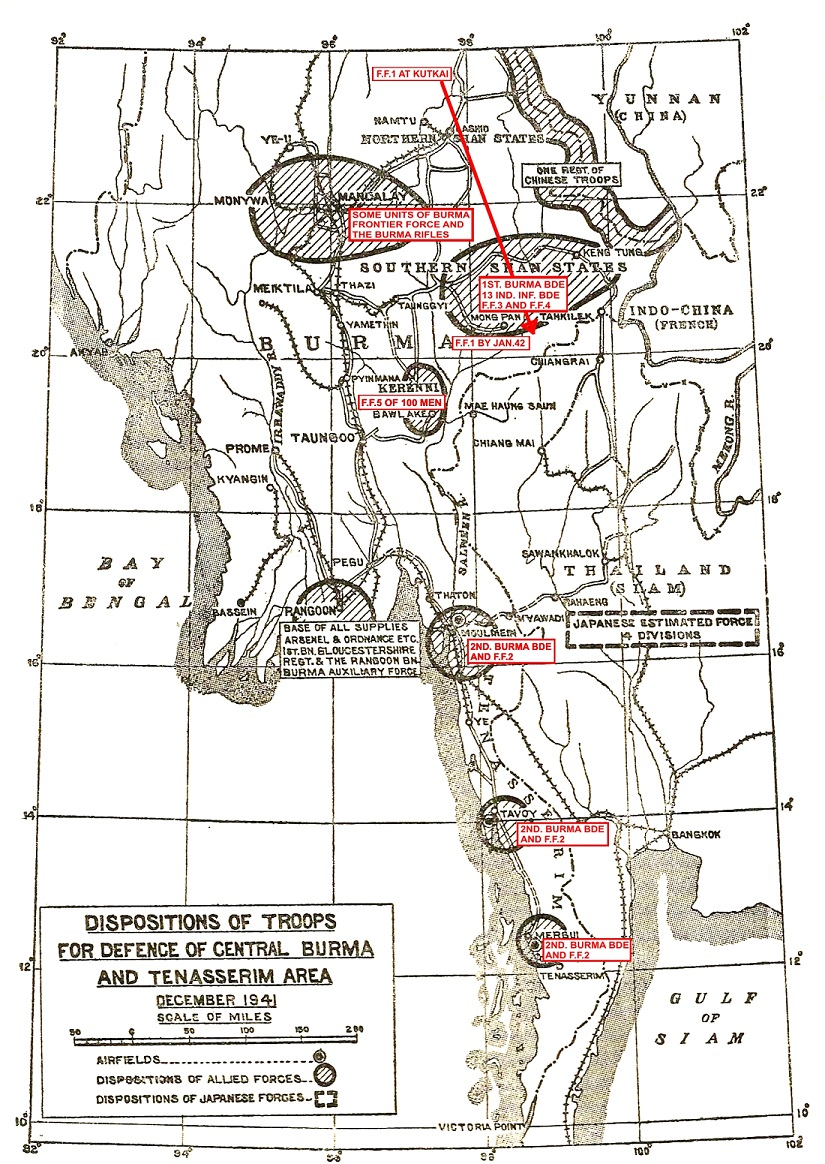

Finally, Slim and Wakely were shown the picture of what Lt-General McLeod’s staff had identified the two most likely routes that the Japanese would take if they did indeed invade. The Southern Shan States were crucial to the protection of the Burma Road to China. The fear was a thrust north eastwards into the Southern Shan States from the Chiengrai-Chiangmai area of Thailand. There were relatively good land communications inside Thailand towards the Burma frontier. Although the routes across the frontier itself were limited to tracks, once inside Burma the Japanese could head straight for the roads on the Tachilek - Keng-Tung –Thazi and the Mongpan-Thazi routes. The 1st Burma Infantry Brigade and the 13th Indian Infantry Brigade were in the Southern Shan States, along with the Burma Frontier Force columns, F.F.3 and F.F.4 protecting that route, with the other two Brigades of 7th Indian Division concentrating at Mandalay from where they could act in defence of the Burma Road.

The other possibility was an attack across the Dawna Hills into Tenasserim, followed by a drive aimed at Rangoon. The 2nd Burma Infantry Brigade, with F.F.2, defended Tenasserim, with significant garrisons at Moulmein, Tavoy and Mergui. This was where the 11th African Division had been sent to man the main line of defence at the Salween River, which was to be held at all costs. Slim’s 10th Indian Division, concentrating at Pegu would back up the 11th African Division. McLeod believed that the difficult border terrain and lack of adequate roads would preclude any serious attack in that direction.

Slim also was informed that the Chinese had offered to send two armies to help defend Burma, the Fifth and Sixth, each about the equivalent on size of a British division but with far less equipment. Auchinleck had accepted this offer but at first wanted these troops to remain inside China but close to the border with Burma where they would provide a reserve until Japanese intentions were revealed. Liaison was established with the Chinese, and it was agreed that one regiment of Chinese troops would move up to the Burma border early in December 1941. This unit was to be available to move into Burma to support the British in the event of a Japanese attack into the Southern Shan States. Auchinleck had agreed for the Chinese 227th Regiment of the Chinese 93rd Division to take over the defence of the Mekong River east of the Kengtung-Mongpyak road, relieving some pressure on Scott’s 1st Burma Brigade.

When General Alexander arrived, there was a great deal to be resolved and finalised. Slim could see some of the potential pitfalls and was reassured by some of his assets. The longer the Japanese delayed invading Burma, the longer the British Empire Forces would have time to prepare. Slim was keen to get to work on making the most of the time he had.

Map from here

The men of 20th Indian Brigade marched out of the port and onto a train to take them to Pegu where 10th Indian Division was being concentrated. The men had been brought to Burma onboard RMS Queen Mary, along with the Division’s artillerymen, engineers and the rest of the men that made up a Division’s fighting ability. The men of 21st and 25th Brigades had sailed on RMS Queen Elizabeth. The two troopships normally ploughed the sea between Australia and the Gulf of Aden. The need to bring the 10th Indian Division to Burma as speedily as possible had meant a detour to Basra. Standing off Rangoon because of the threat of air attack, the men had been transhipped onto other smaller vessels to carry on into the port. General Auchinleck had to fight tooth and nail for the 10th Division to be sent to Burma. With the fighting in Malaya, Percival had been hoping for this Indian Division on top of the recently arrived Australian 9 Division and British 18th Division. General Alexander, newly appointed as GOC Burma Army, had won the argument with the War Office that this Division was crucial to his plan to hold Burma. This, along with Auchinleck’s interventions, had been accepted.

Some of the ships normally used in the Mediterranean between Alexandria and Tobruk and in the Red Sea between Port Sudan and the Suez Canal had been sent to pick up 10th Division’s equipment. These ships, with various escorts, were already in the Bay of Bengal and expected to arrive within the week. Among the equipment was 252nd Indian Armoured Brigade’s mix of light tanks, some well-travelled Vickers A9s and A10s, armoured cars, and 14th/20th King's Hussars’ had M3 Stuart tanks.

Major-General Bill Slim and some of his staff had been in Rangoon for a week trying to sort out all the practicalities of moving and training a Division from one theatre to another. Major-General Arthur Wakely’s 7th Indian Division already had two of its Brigades in Burma. The 13th Brigade had been under the command of the Burma Division. The 16th Brigade was finally complete with all three Battalions concentrated at Mandalay. With the arrival of 14th Brigade, and the Divisional Troops, Wakely, like Slim was trying to get his Division sorted out. The arrival of General Harold Alexander was expected within a day or two. He was currently in Calcutta with General Auchinleck being briefed on the situation, especially about the need to work with the Chinese to keep the Burma Road open.

The other problem that Slim had to deal with was the likelihood that he would be promoted to Lieutenant-General and be put in charge of a newly formed Burma Corps. Slim had requested that General Auchinleck appoint Brigadier Douglas Gracey from 17th Indian Brigade in Iraq to take over as GOC 10th Indian Division. Slim was also aware that a Corps would need a lot more staff that were currently on hand. Auchinleck had negotiated with Wavell to give Alexander help with staff, on top of what he could spare himself from India. Slim had been promised that he would have a proportion of those staff officers when they arrived.

In the meantime, Slim and Wakely had visited Major-General Charles Fowkes (GOC 11th African Division) whose HQ was near Moulmein. They also met with Major-General James Scott (GOC 1st Burma Division). Losing 13th Indian Brigade, Scott was now facing the question about how his two remaining Burmese Brigades would be used. Without Harold Alexander’s input, Slim wasn’t able to say for definite. He admitted that frankly he would like Scott’s men to spend some more time training, both themselves and especially training new arrivals in getting to know, and not fear, the Burmese jungle. Slim was also aware that both Wakely and his men would need translators and local guides. Having some of the Burma Rifles or police on hand would prove very useful.

In discussions among the generals, it became clear to Slim that native Burmans made up a very small percentage of the Burmese forces. Scott noted that his forces (army, police, frontier, auxiliaries, territorials) had over 27000 men, but of that less than 4000 were Burmans. The largest contingent were Indians (over 10000), with substantial numbers of Karens, Chins and Kachins (just under 10000). Scott confirmed what Slim had already been advised by Lieutenant-General Donald McLeod, outgoing GOC (Burma Army), that the political temperature between the various nationalities within Burma was rising. There was a strong independence movement amongst the Burmans, influenced by Gandhi’s Congress Party in India. McLeod’s police had evidence that this was being supported and promoted by the Japanese. There was a real fear that this movement would work at undermining the defence of the country, especially in providing the Japanese with translators and guides. It was even possible that there would be a threat from fifth column activities. All of this made Slim and Wakely keen to enlist Scott’s help to procure reliable locals to support the two Indian formations.

Slim and Wakely were then informed of the existence of the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo officially known as Mission 204 or ‘Tulip Force’. This had been founded to train Australian and British troops in guerrilla warfare for the British Military Mission to China. The secrecy surrounding it came from the time when support for the Chinese was kept as hidden as possible so that there would be no justification for a Japanese attack on the British Empire. Major Michael Calvert was forming his trainees into three Special Service Detachments, or Commandoes. These were all small forces, but available to Slim and Alexander. Calvert was keen on using these commandoes as the Long Range Desert Group had been used in North Africa. The use of irregular troops in the East African campaign had played an interesting role, especially Gideon Force, not one that Slim was terribly keen on, but open to.

Slim was also introduced to the existence of the Oriental Mission, which had been founded in Singapore in May 1941 as the regional headquarters of the Ministry of Economic Warfare. Force 136, as it was known, was designed to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in British territories that might be occupied by an enemy. Slim was informed that they were supporting Lt Col Noel Stevenson who had begun to organise levies from amongst the Karen tribesmen in the Shan States. Stevenson had served with the Burma Frontier Service and had extensive experience of working with the Karens. There was little time, few resources and next to no equipment, but many Karens were being organised to keep watch on Japanese movements and to identify Burmese collaborators. These two pieces of information made Slim realise why General Alexander had asked for Brigadier Orde Wingate to be attached to Burma Command.

Slim noted that having some kind of intelligence gathering system would be crucial and made a note to speak to Alexander about setting up some kind of organisation to provide his Corps with timely and accurate information about Japanese activities and intentions.

As he was new to the area, Slim had paid particular attention to the fact that there was a very limited road network and the railway ran north to south rather than east to west. Slim knew the 11th African Division from East Africa and noted their lower-than-normal establishment of motor vehicles. This was a double-edged issue. On one side, they weren’t tied to the roads so much. On the other side, their movement would be generally slower than a Division with the full allocation of Motor Transport. Slim was interested in how both the Burma Brigades, and the Africans were using more in the way of mules for resupply. Looking at the country, he could see the logic of having ‘all-terrain’ means of getting ammunition, water and rations to units.

The logistics of supporting a force in the east of Burma were going to be difficult. The vast rivers that flowed north to south were useful barriers against an invasion, but the limited bridges and ferries hampered supplying the defenders. There was an obvious danger of traffic jams along the limited roads waiting to cross rivers. This would be an invitation to the Japanese bombers to do great damage with little effort. Slim and Wakely would have to sit down with their staffs and work out how best to make sure the men had adequate supplies at all times.

When the problems had begun in Iraq earlier in the year, the initial forces had been flown into Basra by RAF transports. Slim knew very well the importance of air support, not only in defending troops against the enemy’s bombers, and in attacking the enemy’s troops, but also in re-supplying forces in emergencies. The RAF’s weakness in Burma was a real concern, one that needed more bombers, fighters and transport aircraft. This was out of Slim’s hands, but again something to discuss with Alexander when he arrived.

Something else that would need to be discussed was the threat of malaria and other diseases that would hamper the fighting power of the Indian troops. Slim had been informed by Brigadier Eric Lang, (Director of Medical Services) about the struggles to increase the levels of medical support for the growing army in Burma. Slim knew very well that the health of the troops, keeping the men fit and healthy, would have massive benefits, as would keeping up their morale. While getting more men and equipment was always going to be important, looking after the men and equipment already present was just as important. Until such time as all the reinforcements arrived, Slim had to take as much care for the men under his command as possible.

Finally, Slim and Wakely were shown the picture of what Lt-General McLeod’s staff had identified the two most likely routes that the Japanese would take if they did indeed invade. The Southern Shan States were crucial to the protection of the Burma Road to China. The fear was a thrust north eastwards into the Southern Shan States from the Chiengrai-Chiangmai area of Thailand. There were relatively good land communications inside Thailand towards the Burma frontier. Although the routes across the frontier itself were limited to tracks, once inside Burma the Japanese could head straight for the roads on the Tachilek - Keng-Tung –Thazi and the Mongpan-Thazi routes. The 1st Burma Infantry Brigade and the 13th Indian Infantry Brigade were in the Southern Shan States, along with the Burma Frontier Force columns, F.F.3 and F.F.4 protecting that route, with the other two Brigades of 7th Indian Division concentrating at Mandalay from where they could act in defence of the Burma Road.

The other possibility was an attack across the Dawna Hills into Tenasserim, followed by a drive aimed at Rangoon. The 2nd Burma Infantry Brigade, with F.F.2, defended Tenasserim, with significant garrisons at Moulmein, Tavoy and Mergui. This was where the 11th African Division had been sent to man the main line of defence at the Salween River, which was to be held at all costs. Slim’s 10th Indian Division, concentrating at Pegu would back up the 11th African Division. McLeod believed that the difficult border terrain and lack of adequate roads would preclude any serious attack in that direction.

Slim also was informed that the Chinese had offered to send two armies to help defend Burma, the Fifth and Sixth, each about the equivalent on size of a British division but with far less equipment. Auchinleck had accepted this offer but at first wanted these troops to remain inside China but close to the border with Burma where they would provide a reserve until Japanese intentions were revealed. Liaison was established with the Chinese, and it was agreed that one regiment of Chinese troops would move up to the Burma border early in December 1941. This unit was to be available to move into Burma to support the British in the event of a Japanese attack into the Southern Shan States. Auchinleck had agreed for the Chinese 227th Regiment of the Chinese 93rd Division to take over the defence of the Mekong River east of the Kengtung-Mongpyak road, relieving some pressure on Scott’s 1st Burma Brigade.

When General Alexander arrived, there was a great deal to be resolved and finalised. Slim could see some of the potential pitfalls and was reassured by some of his assets. The longer the Japanese delayed invading Burma, the longer the British Empire Forces would have time to prepare. Slim was keen to get to work on making the most of the time he had.

Map from here

Last edited: