WI: NACA Modified P-38 fighter

-------------------------------------------------------

Notice to Readers: This TL is still alive but only occasionally updated at this time (Summer 2021). Real life and the greatly expanded scope of detail required to continue advancing the TL at this point (including a fair share of original design and research) has kept me from more regular postings. But, Please, follow along and keep your eyes open for updates when they occur. I really value everyone's input and often the discussion around specific developments has been key to finalizing the next development.

Cheers!

E

Jul. 2021

-------------------------------------------------------

(This was something I had planned to post after being on the board longer but a discussion in another thread prompted some discussion of P-38 development so I thought I would go ahead with this for the sake of discussion.)

I know there have been several discussions over the years surrounding the Lockheed P-38 American Twin-Engine fighter/interceptor of WWII but one part of the equation that I have never heard discussed is the “What If…” the NACA recommended modifications to the airplane had been implemented, especially at or near the beginning of P-38 operations.

OTL Background:

Without re-hashing the origin and initial development history of the Lockheed Model 22 / P-38 (all of that information is readily available on numerous on-line sources) I will focus on what led to the NACA studies of the airframe, their proposed solution to the problems encountered, and why these solutions weren’t put in place.

A record-breaking cross-country flight in early 1939 (which resulted in the loss of the only XP-38) garnered enough attention and excitement that the US Army Air Corp (USAAC) placed orders for pre-production (YP-38) and production (P-38) aircraft in numbers greater than Lockheed had anticipated for the entire Model 22 life. This necessitated a rushed production development and major reconfiguration to accommodate the unintended mass-production.

Tests in early 1941 of the first pre-production YP-38’s quickly ran into issues when at high speed (around Mach 0.68), especially in dive, where the nose of the aircraft would drop--locking into an often un-recoverable dive accompanied by “buffeting.” The problems getting the production line up and fully operational prevented Lockheed from directing any engineering resources to these problems until November 1941, but they were unable to identify the cause or provide any solutions until Gen. Hap Arnold, head of the by then renamed Army Air Forces (USAAF), ordered the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA—predecessor of NASA) to analyze the YP-38 in their full-scale wind-tunnel in December 1941 – January 1942 which resulted in the report “Full-Scale Wind-Tunnel Investigation of Buffeting and Diving Tendencies of the YP-38 Airplane.” [EDIT: NASA reorganized its online archives in 2020 so this link is no longer functioning. The upload size limitations on this site prevent me from dropping the file here, but you can find a copy I uploaded at another site, Here]

This report was finally able to identify that the control lock and diving difficulties were the result of a high-speed pressure wake developing over the wing and fuselage resulting is loss of lift to the central wing and buffeting of the tail as the turbulent wake passes over it, a phenomenon just recently discovered at the time which led the idea of the “sound barrier.” This is often referred to a “Compressibility” problem as it related the change of aerodynamics at high speed from a traditional non-compressible fluid to a compressible one. The specific behavior of the P-38 is now better known as “Mach Tuck.”

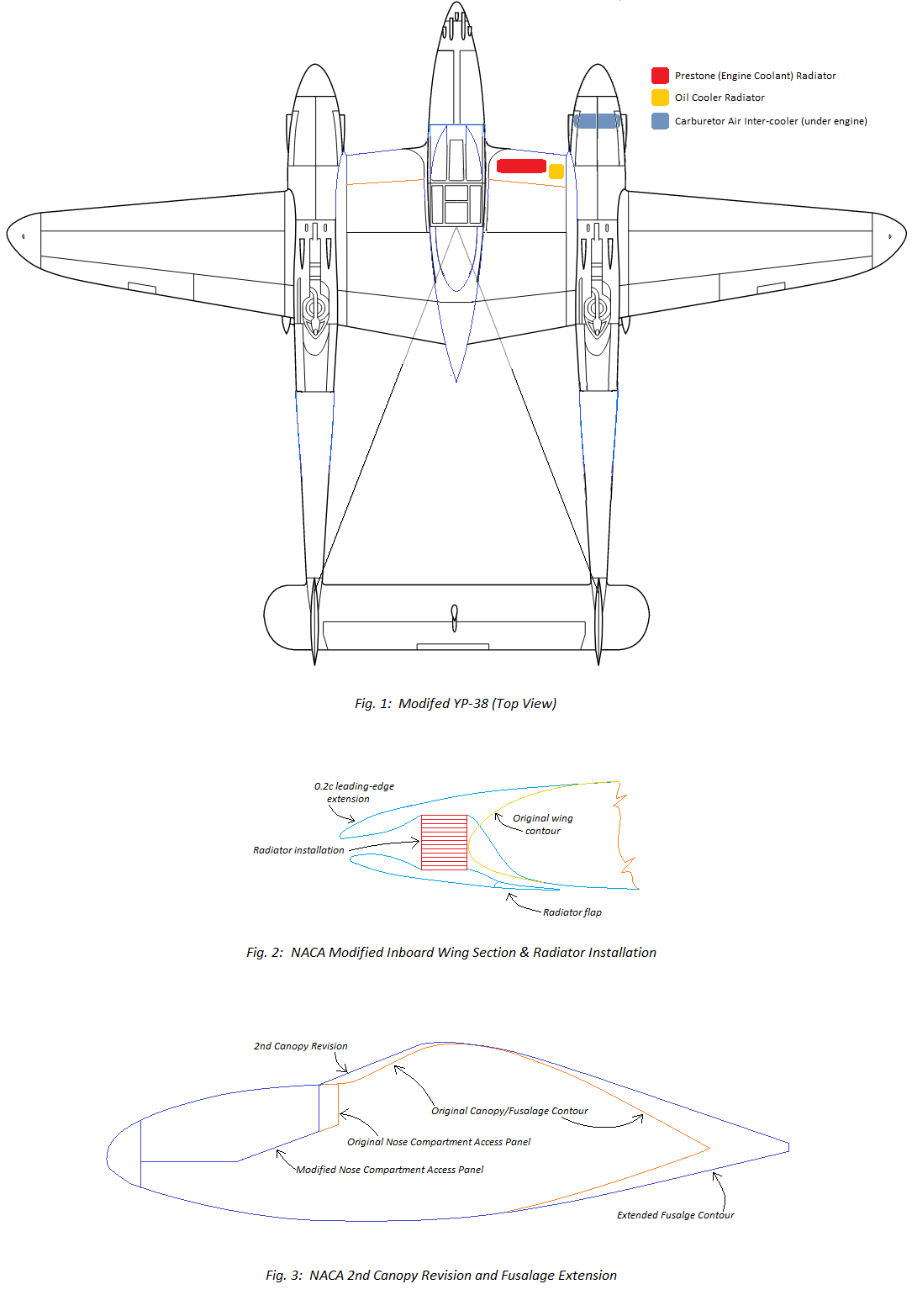

NACA tested several solutions to the problem including wing filleting, partial flap deployment, three different inboard (between the engine booms and the center gondola) wing designs, two revised canopy designs, and an extension to the trailing edge of the gondola. They found the best performance gain (delay of up to 64 mph in the formation of the shock-wave) resulted from a simple 0.2c (20% of chord) leading edge extension to the center wing section and using their second canopy revision. They also noted that although the gondola extension did not increase the Critical Mach number, it did reduce the turbulence of the wake re-joining the airstream and smoothed out the air flow over the tail surfaces.

One aspect which I find very interesting with these design modifications was that the extended leading edge moved the center of lift forward causing the plane to become unbalanced. They recommended moving the coolant radiators from the mid-boom into the extended leading edge of the wing to rebalance the aircraft with the added benefit of reducing drag and further streamlining the aircraft. I will address this again in the ATL discussion to follow.

The problem is that the report wasn’t completed until March 31, 1942, by which time the US was at war and Lockheed was ramping up to start production on the combat-ready P-38F (beginning in April 1942) at war-time production rates. With the P-38 the most capable fighter then in inventory there simply was not the opportunity to re-design and re-tool for the modifications NACA recommended and the P-38 was sent into combat while still suffering numerous problems, not least of which was the issues with compressibility.

The results are well known and documented: the P-38 in the ETO struggled the first 18 months of combat prompting 8th Fighter Command to pre-emptively phase them out in favor of the new P-51 as they became available at the end of 1943 and through the first half of 1944 which prevented Lockheed and the USAAF from implementing a number of fixes for the problems and delayed others until it was too late to have much impact in the reputation of the P-38 in Europe. It was not until the P-38J-25-LO and P-38L-5-LO/VN the airplane really came into its own and that was realized almost entirely in the Pacific.

ATL Discussion:

For this examination of a “What If…” I have decided to place the POD with the NACA study. Specifically, that Gen. Arnold did not wait for Lockheed to tackle the dive issues first and instead ordered the NACA study to take place in June-July of 1941 with the final report completed September 30, 1941 (six months earlier than OTL). This updated timeline would allow Lockheed engineers to immediately go to work implementing the NACA design changes in fall 1941 prior to US entry into the War and the corresponding production pressures which prevented it from happening in OTL. The first production P-38’s with the NACA modifications would then roll out either as late block P-38E’s in early ’42 or, more likely, as the finalized P-38F in April 1942.

OTL, the P-38F/G/H continued to use the enclosed intercooler in the leading edge of the outboard wings, which provided adequate cooling for the early model engines and low-boost ratings but which, by the P-38G and even more so the P-38H, limited engine power to lower settings due to in-adequate cooling. This was a problem that was not anticipated so it wasn’t until the P-38J in August 1943 that the intercoolers were switched to the core-type, chin-mounted position—squeezed between and behind the oil radiators. However, in my ATL, with the oil radiators moved adjacent the coolant radiators in the leading edge extension the space in the chin of the nacelles is completely freed up which allows the core-type intercoolers to be installed in the space previously occupied by the oil radiators as soon as it becomes apparent it is needed without re-designing the nacelles themselves. This means that the engine power limitations of the G either never occurs (because the intercoolers have already been moved) or are quickly overcome by sending field modification kits in early 1943 with full integration on the assembly line taking place with the P-38H in the spring of 1943.

Additionally, moving the intercoolers in these earlier models (G or H) would allow a matching earlier installation of the leading edge fuel tanks in the outer wings, increasing the range and combat radius in 1943 sufficient to provide full escort coverage to 8th AF Bombers even to deep penetration targets.

Another advantage of moving the Prestone (engine coolant) radiators to the inboard position in the extended leading edge is that the heated coolant can be run through a heater core close to the cockpit cupola, increasing available cockpit heat as soon as it becomes apparent the existing heat is insufficient for high-altitude or cold weather operations. Again, this is something I expect would be utilized no later than early-mid 1943.

One final advantage of this layout is that frees up a large amount of space in the tail booms which could be utilized in later production models. With engine weight increases in the F/G and again in the H/J models the Center of Gravity could potentially have been moved forward enough to justify installation of either additional small fuel tanks in the booms where the radiators used to be, or—perhaps a better option—small water/alcohol tanks which would permit the use the Water Injection under War Emergency Power, further increasing performances and reducing the risks of detonation under high manifold pressure (> 60 in/Hg).

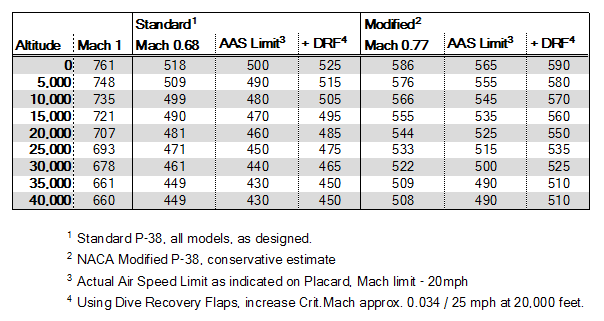

The estimated (conservative according to NACA documents) dive performance gains of this P-38 redesign are impressive:

To put this in perspective, the P-51D had an absolute Critical Mach of around 0.80, depending on the source, but was normally limited to less than 0.73 because of extreme vibrations beyond those speeds. Even if pushing the ’51 to Mach 0.8 or beyond is considered acceptable these NACA estimates for the modified ’38 show a similar diving capability considering a margin for error of the conservative estimate, especially if using Dive Recovery Flaps in addition to the NACA modifications. In these cases the P-38 would be favorable because it can accelerate to max speed faster than the P-51 allowing to either pull-away faster or to gain faster on a diving E/A. Combine that with the faster climb of the P-38, higher peak turning rate, and—in later airplanes—faster roll, there would be nothing that the P-51 could do that the P-38 couldn’t do better. All while bringing a heavier weight of fire on target (128 oz/sec vs 111 oz/sec).

Here are some roughly done drawings of how these modifications would appear (done in MS Paint):

All told, these NACA modifications solve three of the biggest issues with the early combat performance of the P-38 with the 8th Air Force: Limited Dive, Engine Cooling/Reliability, and Cockpit heating. In addition, the lack of the radiator ducts in the booms reduces drag and would likely result in a better level-flight top-speed (I would expect a gain of 10-20 mph from this) and improved/decreased fuel consumption. This leaves only two big problems to solve with later models.

The first of these remaining problems was that the Fuel Mixture, Propeller RPM, and Throttle controls were independent and never had an implemented solution in OTL. For those not familiar with what those are, it means that to change from a “Cruising” condition to a “Combat” condition, the pilot needed to adjust three different levers for each engine (a total of six adjustments): Move Fuel Mixture from Auto-Lean to Auto-Rich; Increase Propeller RPMs; Increase manifold pressure (throttle). I have read some anecdotal evidence* that Lockheed had developed an “automatic manifold pressure regulator” which automated all of these adjustments into a single lever per engine but that the Air Force deemed it “unnecessary” and never authorized its implementation (Allison, the engine manufacturer, implemented this system on the post-war “G” series V-1710 engines). Supposing, with the “big three” problems solved due to the NACA redesign early in the combat life of the airplane the 8th AF decided to keep the P-38’s in primary service longer it is reasonable, I think, to assume this modification would become “necessary” and it could be implemented by late 1943/early 1944 models of the airplane (OTL P-38J, but in ATL, probably be considered second or third block P-38H).

The second remaining issue was that the ailerons became heavy at high speeds and the so the airplane’s roll rate was quite slow, limiting its use as a dog-fighter. In OTL this was fixed in June 1944 with the P-38J-25-LO which introduced hydraulically boosted ailerons. These exponentially increased the force on the ailerons when turning the yoke and allowed the P-38 to flick-roll faster than most other fighters of the time. I am not certain how much more quickly these would be introduced in ATL vs. OTL as the slow-roll performance wouldn’t be altered by the NACA modifications nor was its solution delayed or prevented by AF brass. So, let’s say that this modification is introduced as it was in OTL, i.e. June 1944.

Finally, with the 8th AF decision to keep the P-38 as the primary long-range escort fighter I believe it is reasonable to presume that they would have dedicated more time and resources to addressing the basic and tactical training for the pilots that was largely ignored in OTL, possibly even to the extant to sharing information with the P-38 FGs in the PTO—although that is uncertain.

The result is, that when the 55th FG is transferred to the 8th AF with P-38H’s in September 1943 they have an aircraft capable of escorting bombers, at high-altitude, comfortably, reliably, and with significantly improved performance over most Axis fighters. This would reduce the demand for P-51’s and while I still expect them to come in theatre I would expect the P-38 Fighter Groups to keep the P-38’s rather than switching to P-47’s and P-51’s resulting in a near even three-way split between the fighter types by war’s end.

I don’t know that this would have any significant impact on the eventual course or outcome of the war but improved long-range escort earlier in the war could have had a large positive impact on bomber-loss rates and morale. The reduction in bomber-losses in turn could mean a faster buildup of US Bomber forces and an earlier launch of major 1000+ raids perhaps even increasing the time-table for the Normandy Invasion, although other logistical problems likely lock that in no earlier than May ’44.

The biggest difference would be in the reception and memory of the P-38 and its potential for a continued career post-war, similar to the P-51. The possibility of keeping them in service longer could also lead to the late-war approval for the adoption of the P-38K-1 with the F15 (Allison V-1710-75/77) engines and Hamilton-Standard Hydromatic high-activity propellers. In OTL only one of these was made using the large P-38J style chin and retaining the high-drag boom radiators. Even with all that drag it was able to achieve 432mph in level flight using Military Power and was expected to make 450mph with War Emergency Power with matching improvements in range and fuel consumption (about 10%). It also had a ceiling of 46,000 feet, a max climb of 4,800 ft/minute and could make it to 20,000 feet in only five minutes. Without the full coat of pain and with the reduced drag of the NACA design modification I can only image what its performance could be. In this case the P-38K would likely replace the F/P-82 Twin-Mustang of OTL and see continued service into the early 1950’s including limited combat in Korea as bomber-escorts and Close Air Support.

So, any thoughts on this, its feasibility, and any effects I may have missed?

-----------------------

* http://www.ausairpower.net/P-38-Analysis.html (Pertinent section about 45% down in the italicized letter from Col. Harold J. Rau to “Commanding General, VIII Fighter Command, APO 637, U.S. Army”)

-------------------------------------------------------

Notice to Readers: This TL is still alive but only occasionally updated at this time (Summer 2021). Real life and the greatly expanded scope of detail required to continue advancing the TL at this point (including a fair share of original design and research) has kept me from more regular postings. But, Please, follow along and keep your eyes open for updates when they occur. I really value everyone's input and often the discussion around specific developments has been key to finalizing the next development.

Cheers!

E

Jul. 2021

-------------------------------------------------------

(This was something I had planned to post after being on the board longer but a discussion in another thread prompted some discussion of P-38 development so I thought I would go ahead with this for the sake of discussion.)

I know there have been several discussions over the years surrounding the Lockheed P-38 American Twin-Engine fighter/interceptor of WWII but one part of the equation that I have never heard discussed is the “What If…” the NACA recommended modifications to the airplane had been implemented, especially at or near the beginning of P-38 operations.

OTL Background:

Without re-hashing the origin and initial development history of the Lockheed Model 22 / P-38 (all of that information is readily available on numerous on-line sources) I will focus on what led to the NACA studies of the airframe, their proposed solution to the problems encountered, and why these solutions weren’t put in place.

A record-breaking cross-country flight in early 1939 (which resulted in the loss of the only XP-38) garnered enough attention and excitement that the US Army Air Corp (USAAC) placed orders for pre-production (YP-38) and production (P-38) aircraft in numbers greater than Lockheed had anticipated for the entire Model 22 life. This necessitated a rushed production development and major reconfiguration to accommodate the unintended mass-production.

Tests in early 1941 of the first pre-production YP-38’s quickly ran into issues when at high speed (around Mach 0.68), especially in dive, where the nose of the aircraft would drop--locking into an often un-recoverable dive accompanied by “buffeting.” The problems getting the production line up and fully operational prevented Lockheed from directing any engineering resources to these problems until November 1941, but they were unable to identify the cause or provide any solutions until Gen. Hap Arnold, head of the by then renamed Army Air Forces (USAAF), ordered the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA—predecessor of NASA) to analyze the YP-38 in their full-scale wind-tunnel in December 1941 – January 1942 which resulted in the report “Full-Scale Wind-Tunnel Investigation of Buffeting and Diving Tendencies of the YP-38 Airplane.” [EDIT: NASA reorganized its online archives in 2020 so this link is no longer functioning. The upload size limitations on this site prevent me from dropping the file here, but you can find a copy I uploaded at another site, Here]

This report was finally able to identify that the control lock and diving difficulties were the result of a high-speed pressure wake developing over the wing and fuselage resulting is loss of lift to the central wing and buffeting of the tail as the turbulent wake passes over it, a phenomenon just recently discovered at the time which led the idea of the “sound barrier.” This is often referred to a “Compressibility” problem as it related the change of aerodynamics at high speed from a traditional non-compressible fluid to a compressible one. The specific behavior of the P-38 is now better known as “Mach Tuck.”

NACA tested several solutions to the problem including wing filleting, partial flap deployment, three different inboard (between the engine booms and the center gondola) wing designs, two revised canopy designs, and an extension to the trailing edge of the gondola. They found the best performance gain (delay of up to 64 mph in the formation of the shock-wave) resulted from a simple 0.2c (20% of chord) leading edge extension to the center wing section and using their second canopy revision. They also noted that although the gondola extension did not increase the Critical Mach number, it did reduce the turbulence of the wake re-joining the airstream and smoothed out the air flow over the tail surfaces.

One aspect which I find very interesting with these design modifications was that the extended leading edge moved the center of lift forward causing the plane to become unbalanced. They recommended moving the coolant radiators from the mid-boom into the extended leading edge of the wing to rebalance the aircraft with the added benefit of reducing drag and further streamlining the aircraft. I will address this again in the ATL discussion to follow.

The problem is that the report wasn’t completed until March 31, 1942, by which time the US was at war and Lockheed was ramping up to start production on the combat-ready P-38F (beginning in April 1942) at war-time production rates. With the P-38 the most capable fighter then in inventory there simply was not the opportunity to re-design and re-tool for the modifications NACA recommended and the P-38 was sent into combat while still suffering numerous problems, not least of which was the issues with compressibility.

The results are well known and documented: the P-38 in the ETO struggled the first 18 months of combat prompting 8th Fighter Command to pre-emptively phase them out in favor of the new P-51 as they became available at the end of 1943 and through the first half of 1944 which prevented Lockheed and the USAAF from implementing a number of fixes for the problems and delayed others until it was too late to have much impact in the reputation of the P-38 in Europe. It was not until the P-38J-25-LO and P-38L-5-LO/VN the airplane really came into its own and that was realized almost entirely in the Pacific.

ATL Discussion:

For this examination of a “What If…” I have decided to place the POD with the NACA study. Specifically, that Gen. Arnold did not wait for Lockheed to tackle the dive issues first and instead ordered the NACA study to take place in June-July of 1941 with the final report completed September 30, 1941 (six months earlier than OTL). This updated timeline would allow Lockheed engineers to immediately go to work implementing the NACA design changes in fall 1941 prior to US entry into the War and the corresponding production pressures which prevented it from happening in OTL. The first production P-38’s with the NACA modifications would then roll out either as late block P-38E’s in early ’42 or, more likely, as the finalized P-38F in April 1942.

OTL, the P-38F/G/H continued to use the enclosed intercooler in the leading edge of the outboard wings, which provided adequate cooling for the early model engines and low-boost ratings but which, by the P-38G and even more so the P-38H, limited engine power to lower settings due to in-adequate cooling. This was a problem that was not anticipated so it wasn’t until the P-38J in August 1943 that the intercoolers were switched to the core-type, chin-mounted position—squeezed between and behind the oil radiators. However, in my ATL, with the oil radiators moved adjacent the coolant radiators in the leading edge extension the space in the chin of the nacelles is completely freed up which allows the core-type intercoolers to be installed in the space previously occupied by the oil radiators as soon as it becomes apparent it is needed without re-designing the nacelles themselves. This means that the engine power limitations of the G either never occurs (because the intercoolers have already been moved) or are quickly overcome by sending field modification kits in early 1943 with full integration on the assembly line taking place with the P-38H in the spring of 1943.

Additionally, moving the intercoolers in these earlier models (G or H) would allow a matching earlier installation of the leading edge fuel tanks in the outer wings, increasing the range and combat radius in 1943 sufficient to provide full escort coverage to 8th AF Bombers even to deep penetration targets.

Another advantage of moving the Prestone (engine coolant) radiators to the inboard position in the extended leading edge is that the heated coolant can be run through a heater core close to the cockpit cupola, increasing available cockpit heat as soon as it becomes apparent the existing heat is insufficient for high-altitude or cold weather operations. Again, this is something I expect would be utilized no later than early-mid 1943.

One final advantage of this layout is that frees up a large amount of space in the tail booms which could be utilized in later production models. With engine weight increases in the F/G and again in the H/J models the Center of Gravity could potentially have been moved forward enough to justify installation of either additional small fuel tanks in the booms where the radiators used to be, or—perhaps a better option—small water/alcohol tanks which would permit the use the Water Injection under War Emergency Power, further increasing performances and reducing the risks of detonation under high manifold pressure (> 60 in/Hg).

The estimated (conservative according to NACA documents) dive performance gains of this P-38 redesign are impressive:

To put this in perspective, the P-51D had an absolute Critical Mach of around 0.80, depending on the source, but was normally limited to less than 0.73 because of extreme vibrations beyond those speeds. Even if pushing the ’51 to Mach 0.8 or beyond is considered acceptable these NACA estimates for the modified ’38 show a similar diving capability considering a margin for error of the conservative estimate, especially if using Dive Recovery Flaps in addition to the NACA modifications. In these cases the P-38 would be favorable because it can accelerate to max speed faster than the P-51 allowing to either pull-away faster or to gain faster on a diving E/A. Combine that with the faster climb of the P-38, higher peak turning rate, and—in later airplanes—faster roll, there would be nothing that the P-51 could do that the P-38 couldn’t do better. All while bringing a heavier weight of fire on target (128 oz/sec vs 111 oz/sec).

Here are some roughly done drawings of how these modifications would appear (done in MS Paint):

All told, these NACA modifications solve three of the biggest issues with the early combat performance of the P-38 with the 8th Air Force: Limited Dive, Engine Cooling/Reliability, and Cockpit heating. In addition, the lack of the radiator ducts in the booms reduces drag and would likely result in a better level-flight top-speed (I would expect a gain of 10-20 mph from this) and improved/decreased fuel consumption. This leaves only two big problems to solve with later models.

The first of these remaining problems was that the Fuel Mixture, Propeller RPM, and Throttle controls were independent and never had an implemented solution in OTL. For those not familiar with what those are, it means that to change from a “Cruising” condition to a “Combat” condition, the pilot needed to adjust three different levers for each engine (a total of six adjustments): Move Fuel Mixture from Auto-Lean to Auto-Rich; Increase Propeller RPMs; Increase manifold pressure (throttle). I have read some anecdotal evidence* that Lockheed had developed an “automatic manifold pressure regulator” which automated all of these adjustments into a single lever per engine but that the Air Force deemed it “unnecessary” and never authorized its implementation (Allison, the engine manufacturer, implemented this system on the post-war “G” series V-1710 engines). Supposing, with the “big three” problems solved due to the NACA redesign early in the combat life of the airplane the 8th AF decided to keep the P-38’s in primary service longer it is reasonable, I think, to assume this modification would become “necessary” and it could be implemented by late 1943/early 1944 models of the airplane (OTL P-38J, but in ATL, probably be considered second or third block P-38H).

The second remaining issue was that the ailerons became heavy at high speeds and the so the airplane’s roll rate was quite slow, limiting its use as a dog-fighter. In OTL this was fixed in June 1944 with the P-38J-25-LO which introduced hydraulically boosted ailerons. These exponentially increased the force on the ailerons when turning the yoke and allowed the P-38 to flick-roll faster than most other fighters of the time. I am not certain how much more quickly these would be introduced in ATL vs. OTL as the slow-roll performance wouldn’t be altered by the NACA modifications nor was its solution delayed or prevented by AF brass. So, let’s say that this modification is introduced as it was in OTL, i.e. June 1944.

Finally, with the 8th AF decision to keep the P-38 as the primary long-range escort fighter I believe it is reasonable to presume that they would have dedicated more time and resources to addressing the basic and tactical training for the pilots that was largely ignored in OTL, possibly even to the extant to sharing information with the P-38 FGs in the PTO—although that is uncertain.

The result is, that when the 55th FG is transferred to the 8th AF with P-38H’s in September 1943 they have an aircraft capable of escorting bombers, at high-altitude, comfortably, reliably, and with significantly improved performance over most Axis fighters. This would reduce the demand for P-51’s and while I still expect them to come in theatre I would expect the P-38 Fighter Groups to keep the P-38’s rather than switching to P-47’s and P-51’s resulting in a near even three-way split between the fighter types by war’s end.

I don’t know that this would have any significant impact on the eventual course or outcome of the war but improved long-range escort earlier in the war could have had a large positive impact on bomber-loss rates and morale. The reduction in bomber-losses in turn could mean a faster buildup of US Bomber forces and an earlier launch of major 1000+ raids perhaps even increasing the time-table for the Normandy Invasion, although other logistical problems likely lock that in no earlier than May ’44.

The biggest difference would be in the reception and memory of the P-38 and its potential for a continued career post-war, similar to the P-51. The possibility of keeping them in service longer could also lead to the late-war approval for the adoption of the P-38K-1 with the F15 (Allison V-1710-75/77) engines and Hamilton-Standard Hydromatic high-activity propellers. In OTL only one of these was made using the large P-38J style chin and retaining the high-drag boom radiators. Even with all that drag it was able to achieve 432mph in level flight using Military Power and was expected to make 450mph with War Emergency Power with matching improvements in range and fuel consumption (about 10%). It also had a ceiling of 46,000 feet, a max climb of 4,800 ft/minute and could make it to 20,000 feet in only five minutes. Without the full coat of pain and with the reduced drag of the NACA design modification I can only image what its performance could be. In this case the P-38K would likely replace the F/P-82 Twin-Mustang of OTL and see continued service into the early 1950’s including limited combat in Korea as bomber-escorts and Close Air Support.

So, any thoughts on this, its feasibility, and any effects I may have missed?

-----------------------

* http://www.ausairpower.net/P-38-Analysis.html (Pertinent section about 45% down in the italicized letter from Col. Harold J. Rau to “Commanding General, VIII Fighter Command, APO 637, U.S. Army”)

Last edited: