When did the Hawaiian monarchy return? I have to say the flag is a bit ugly, but this can partially go along with why so many countries and island colonies kept the Union Jack when it went with a blue flag (perhaps going along with their hole island vibe) but red... You know, I wish that there were some countries or colonies that had ended up a white flag to go with the Union Jack (even if people would worry it looked like a white flag of surrender.), as then Hawaii with its stripes would be seen as a perfect middleground. I do see you kept those in the coat of arms which is a nice touch. It would be interesting to see a full coat of arms, but that would be waaaaay too complicated to make. I am guessing the Mariannes contain Guam here? Did the Japanese end up with the Philippines? WWII would have been somewhat difficult for the British if they did not have the military and economy of the United States helping them out in the PacificA quick one:

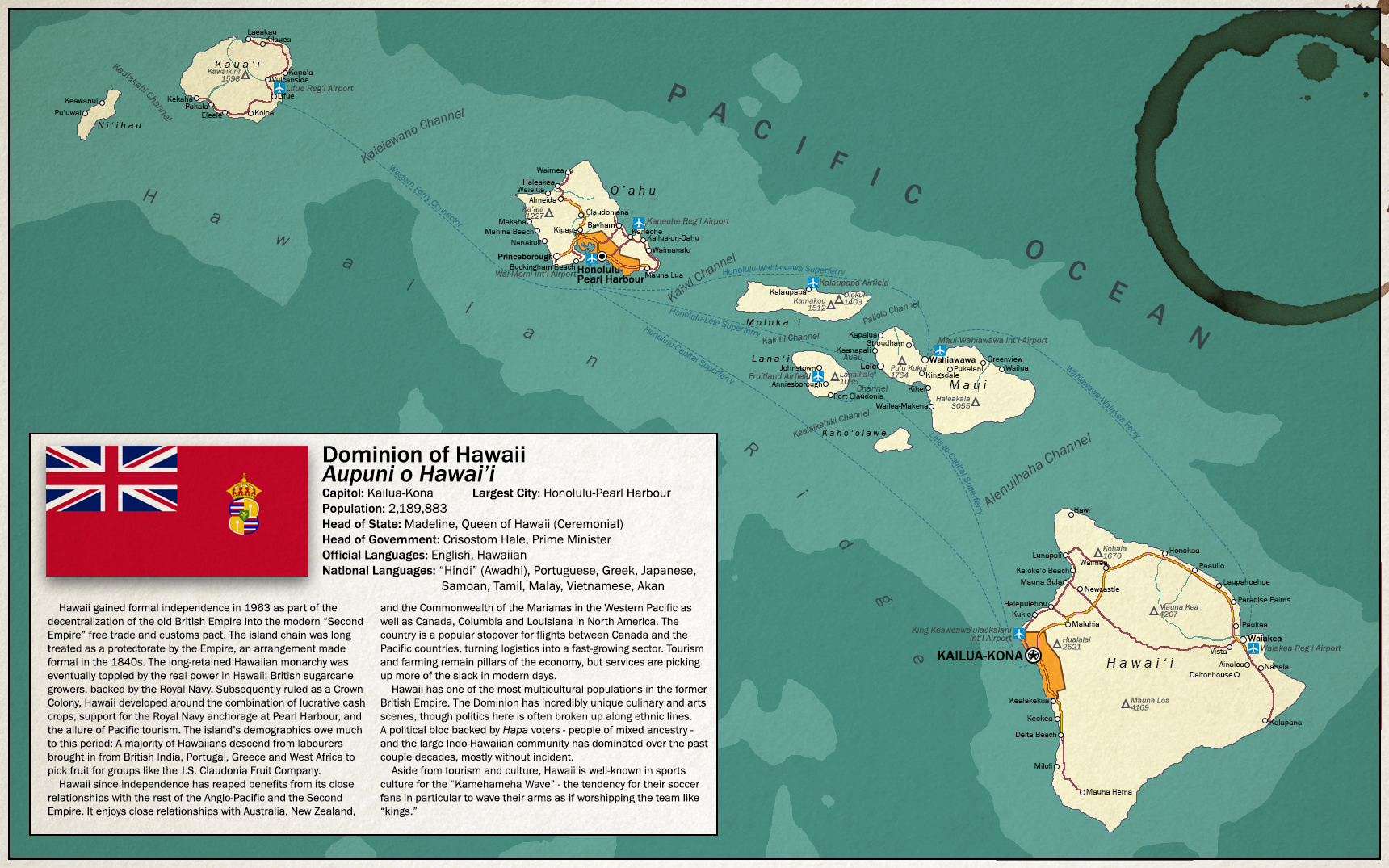

Hawaii in Giant Canada World, part of the broader Anglo-Pacific world by way of volumes of immigrants from India and the Mediterranean. Sadly the Hawaiian monarchy didn't survive the scheming of British sugarcane planters and the Royal Navy in the late 1800s, by which time the British public wanted their canned pineapple and didn't much care how they got it. GCW Hawaii is less wealthy than OTL, with its politics partially divided into ethnic blocs. More of the archipelago is owned by the public after various buyouts from rich fruit company heirs over the years. The Canadian and British Navies still park in Pearl Harbour (with a U) because Hawaii isn't exactly a military powerhouse beyond a few coastal patrol boats. Hawaii's one of those places that gets some advantage from the Second Empire trade pact that the British Empire has evolved into: A lot of people from the bigger Pacific and North American parts of the Anglosphere show up here in winter because the customs barriers to traveling within the pact countries are quite low.

Also whoever put down their coffee on the map, I'm gonna drink it. I'm gonna drink it all up.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Map Thread XXII

- Thread starter Balkanized U.S.A

- Start date

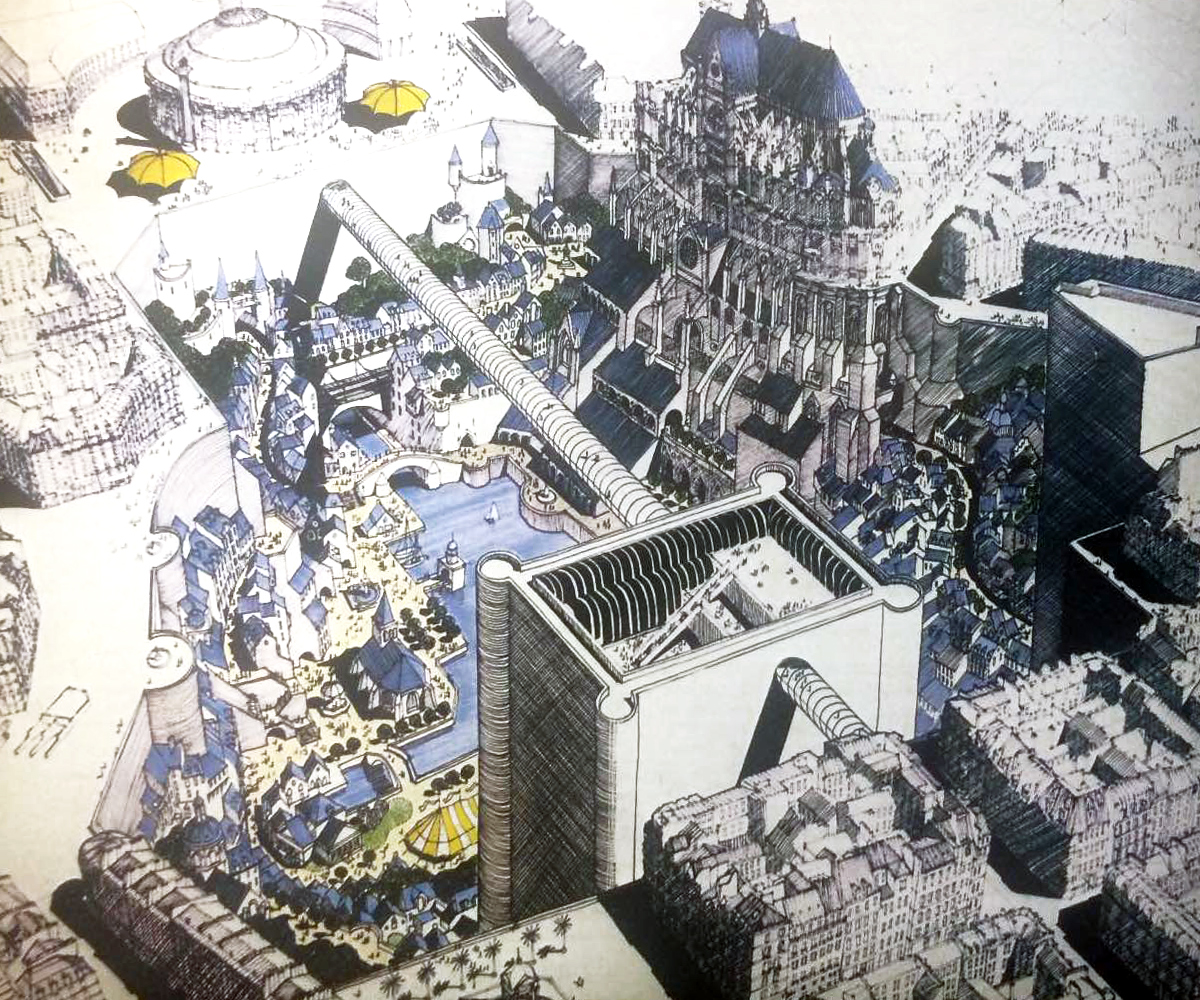

If Walt Disney personally designed Euro-Disneyland.1980 design for Les Halles in Paris, France by Jean Patou

(Does this count?)

Planet of Hats

Donor

The Hawaiian monarchy didn't come back. They were overthrown by the fruit plantation class and the Royal Navy in the late 1800s. Hawaii recognizes the British crown now.When did the Hawaiian monarchy return? I have to say the flag is a bit ugly, but this can partially go along with why so many countries and island colonies kept the Union Jack when it went with a blue flag (perhaps going along with their hole island vibe) but red... You know, I wish that there were some countries or colonies that had ended up a white flag to go with the Union Jack (even if people would worry it looked like a white flag of surrender.), as then Hawaii with its stripes would be seen as a perfect middleground. I do see you kept those in the coat of arms which is a nice touch. It would be interesting to see a full coat of arms, but that would be waaaaay too complicated to make. I am guessing the Mariannes contain Guam here? Did the Japanese end up with the Philippines? WWII would have been somewhat difficult for the British if they did not have the military and economy of the United States helping them out in the Pacific

There was no "World War II" but Britain did have help in the Great World War's Pacific theatre from Giant Canada, Columbia and California in particular. Japan did not get the Philippines and China came out more organized and better able to fight.

Not seeing much mapping here.1980 design for Les Halles in Paris, France by Jean Patou

(Does this count?)

Oh, there’s an idea. Do we have an “alternate buildings“ thread already? We’ve had diagrams of Epcot here and blueprints of memorials that were never built. Would they not be “maps” in the strictest sense?Not seeing much mapping here.

We have a specific Unbuilt Britain and, inspired by it, Unbuilt Canada and Unbuilt Australia were created last month, but I'm not aware of a general thread for alternate or unbuilt buildings.Do we have an “alternate buildings“ thread already?

Bytor

Monthly Donor

People should still take care to include credit.Its the Map Thread, not the Original Cartography Work Thread

This would be much more appropriate for the "Proposals and War Aims That Didn't Happen Map Thread"Oh, there’s an idea. Do we have an “alternate buildings“ thread already? We’ve had diagrams of Epcot here and blueprints of memorials that were never built. Would they not be “maps” in the strictest sense?

Nah, it' an independent Tunisia.I'm curious as to how Italy managed to snag a protectorate over Tunisia, considering it was French.

Building designs are a sort of map. "a diagrammatic representation of an area of land or sea showing physical features, cities, roads, etc."Not seeing much mapping here.

Not classically but buildings are a grey area in the thread.

Sarawak was promoted as a dominions after being already de facto independent.Is that a Territory of Sarawak? Or independent?

Karl der Große

Banned

If people can't properly attribute maps, we shouldn't post those maps.Its the Map Thread, not the Original Cartography Work Thread

How often does that actually happen?If people can't properly attribute maps, we shouldn't post those maps.

Its the Map Thread, not the Original Cartography Work Thread

For a very long time that WAS how the map thread worked, we even maintained several other threads for maps we didn't create ourself.

"The Last Man in Europe (also published as The Last Man) is a dystopian novel and cautionary tale by English writer Eric Arthur Blair (1903 - 1984). It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Blair's ninth book. The story takes place in an imagined future in an unspecified year where Great Britain, now known as Airstrip One, has become a totalitarian state ruled by "The Party". Using omnipresent government surveillance through the Thought Police, and historical negationism and constant propaganda through the Ministry of Truth, the Party persecutes individuality and independent thinking."

Top ExtraNet Searches (December 2183):

1. Emmanuel Goldstein Nobel Peace Prize

2. Brazil membership in Trans-Oceanic Compact

3. Eurasian Legislative Elections

4. Pan-Asianism

5. Holiday in the Malabar Coast

- Seven Members at present: the North American Union, the British Commonwealth, the South African Federation, the Pacific Union, The Republic of Ireland, Iceland & Greenland, and the Federated States of Micronesia.

- Currently pending membership applications: Brazil, Madagascar, Cape Verde, Mauritius, and the Seychelles.

- Aligned nations include (most notably) the Union of India, an alliance stemming from Delhi feeling enroached upon by Eurasia and China.

The Eurasian Union of Soviet Republics

- The initial signatories of the Third Union Treaty (2055) consisted of the Union of Sovereign Soviet Republics and the other members of the Warsaw Pact. Afghanistan's ratification of the treaty in 2127 was the most recent.

- Iran and Turkey currently seek ascension to the Eurasian Union and are currently in negotiations with Moscow. They are expected to ratify the Third Union Treaty by 2186.

- Eurasia maintains a very close relationship with the European Union; one so friendly that the prospect of a "Fourth Union Treaty" merging the two is a "terrifying probability" according to many TOC foreign policy experts. It's often assumed such a merger will include the Federal Republic of Germany, in spite of its official status of neutrality since its reunification in 2005.

China

- Has massively rehabilitated itself since the mess that was the Third World War (2045 - 2047).

- Currently the de-facto leader of the Asia-Pacific Economic Community. Attempts at an EU-style federalization have stalled at present, though are expected to be kicked back to life come the 23rd Century.

- Recent overtures to the East African Federation and various Latin American nations have been noted and are being closely observed by the TOC and Eurasia.

The Non-Aligned Movement

- Mainly consists of members of the Federation of the Americas, the Arab League, and the African Union.

- Depicted on the map are the commonly observed regional blocs of the aforementioned organizations.

POD: Vaguely in the 1940s; either during or shortly after WW2.

Concept: A tongue-in-cheek and actually rather optimistic Alternate/Future History setting very loosely inspired by the rough (and alleged) geopolitical situation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

...

Top ExtraNet Searches (December 2183):

1. Emmanuel Goldstein Nobel Peace Prize

2. Brazil membership in Trans-Oceanic Compact

3. Eurasian Legislative Elections

4. Pan-Asianism

5. Holiday in the Malabar Coast

...

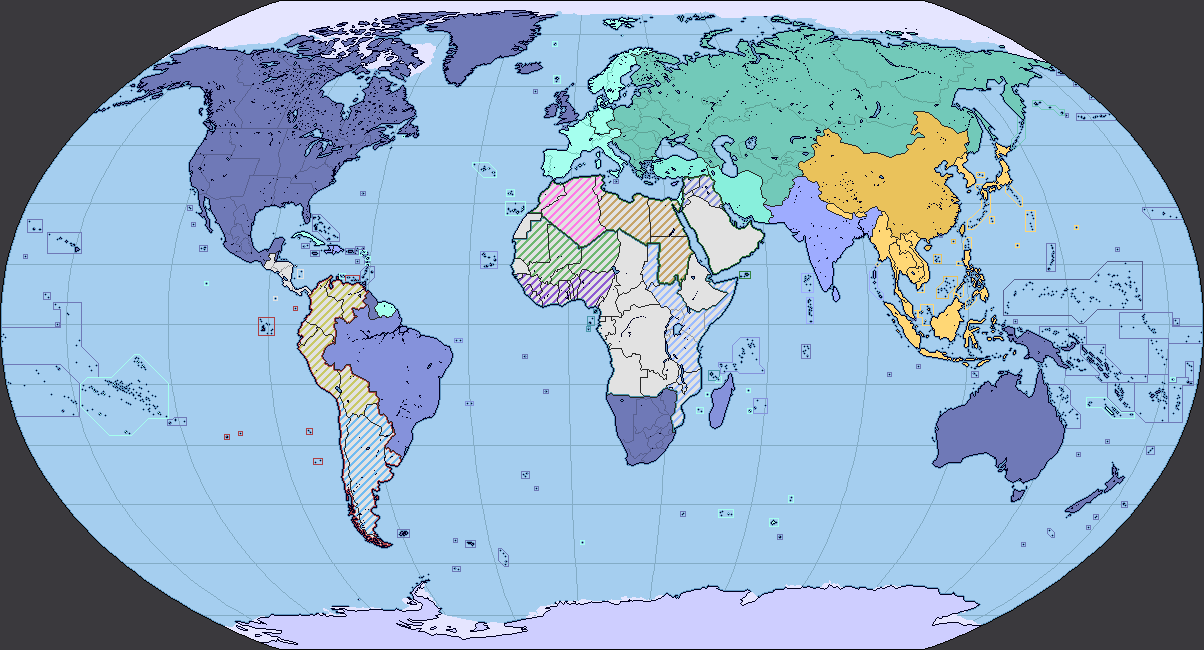

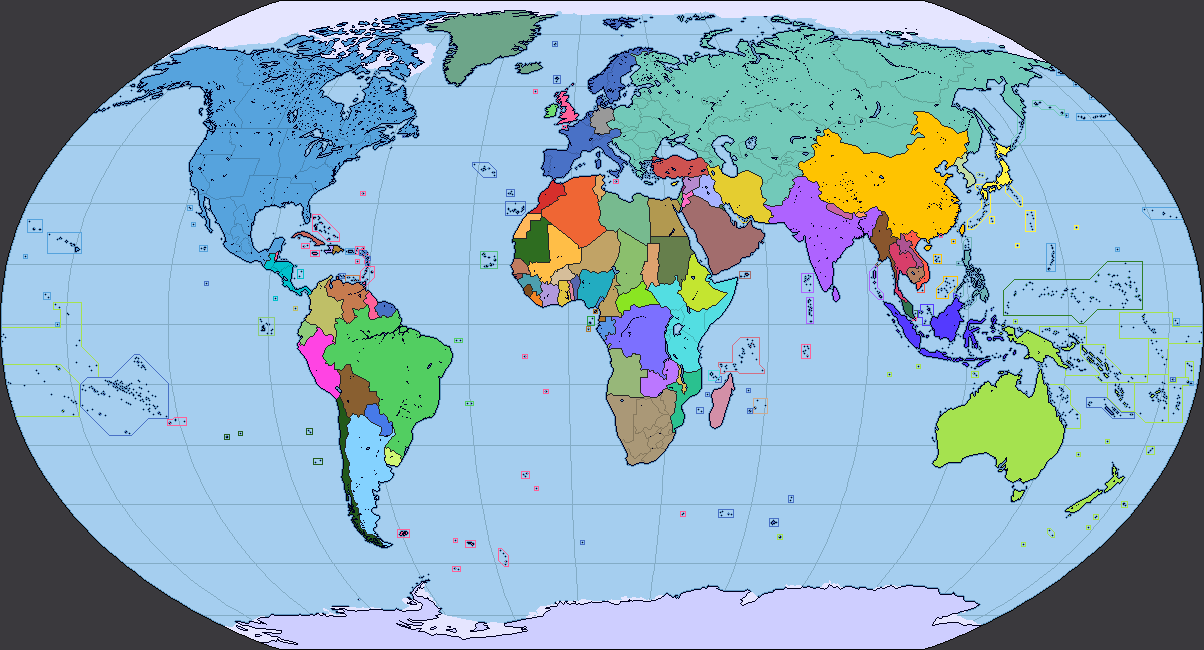

ATLAS OF THE WORLD (2183 CE)

...

ATLAS OF THE WORLD (2183 CE)

...

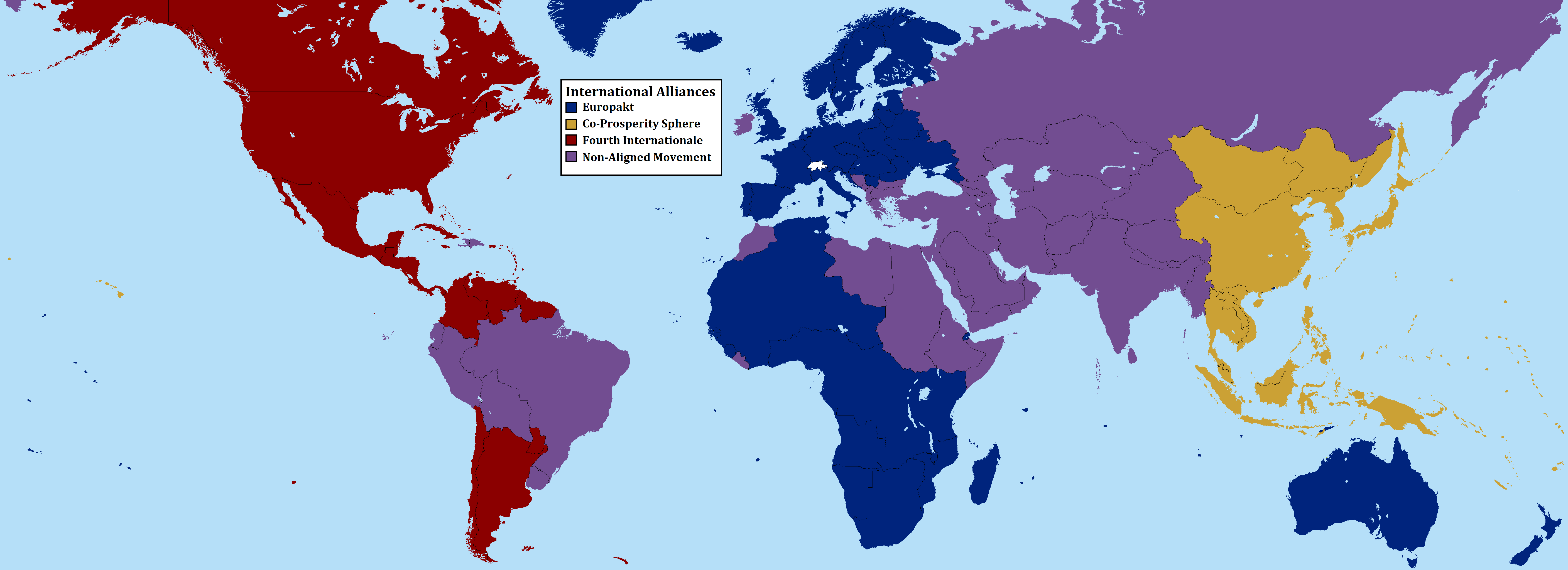

MAJOR GEOPOLITICAL BLOCS OF THE LATE 22ND CENTURY

The Trans-Oceanic Compact

- Seven Members at present: the North American Union, the British Commonwealth, the South African Federation, the Pacific Union, The Republic of Ireland, Iceland & Greenland, and the Federated States of Micronesia.

- Currently pending membership applications: Brazil, Madagascar, Cape Verde, Mauritius, and the Seychelles.

- Aligned nations include (most notably) the Union of India, an alliance stemming from Delhi feeling enroached upon by Eurasia and China.

The Eurasian Union of Soviet Republics

- The initial signatories of the Third Union Treaty (2055) consisted of the Union of Sovereign Soviet Republics and the other members of the Warsaw Pact. Afghanistan's ratification of the treaty in 2127 was the most recent.

- Iran and Turkey currently seek ascension to the Eurasian Union and are currently in negotiations with Moscow. They are expected to ratify the Third Union Treaty by 2186.

- Eurasia maintains a very close relationship with the European Union; one so friendly that the prospect of a "Fourth Union Treaty" merging the two is a "terrifying probability" according to many TOC foreign policy experts. It's often assumed such a merger will include the Federal Republic of Germany, in spite of its official status of neutrality since its reunification in 2005.

China

- Has massively rehabilitated itself since the mess that was the Third World War (2045 - 2047).

- Currently the de-facto leader of the Asia-Pacific Economic Community. Attempts at an EU-style federalization have stalled at present, though are expected to be kicked back to life come the 23rd Century.

- Recent overtures to the East African Federation and various Latin American nations have been noted and are being closely observed by the TOC and Eurasia.

The Non-Aligned Movement

- Mainly consists of members of the Federation of the Americas, the Arab League, and the African Union.

- Depicted on the map are the commonly observed regional blocs of the aforementioned organizations.

...

POD: Vaguely in the 1940s; either during or shortly after WW2.

Concept: A tongue-in-cheek and actually rather optimistic Alternate/Future History setting very loosely inspired by the rough (and alleged) geopolitical situation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Last edited:

The following scenario and maps are based on a game of Hearts of Iron IV: Kaiserreich I played recently, as the Ottoman Empire. It’s not 1:1 like how the game went, but the basic scenario begins with a Central Powers victory in WW1 a la the world of Kaiserreich.

Full write-up below the cut, but the TL;DR of the story is:

The full story write-up (it came out longer than expected):

Members of the international alliances:

Full write-up below the cut, but the TL;DR of the story is:

- Economic crisis in Germany leads to German hegemony gradually unravelling throughout the world

- This is taken advantage of by a nationalist Russia, and syndicalist France, each building their own power blocs in preparation for eventual war with Germany

- The socialists win the Spanish Civil War, there’s a revolution in the Netherlands, the Baltic Duchy breaks up and is swallowed by nationalist Russia, Bulgaria is partitioned among its neighbors, and the Austro-Hungarian empire collapses under the weight of its own contradictions.

- Kemalist Ottoman Empire is in the process of modernizing, when it is attacked by an anti-Ottoman coalition consisting of Egypt, socialist Persia, Georgia, Greece, Yemen, Cyrenaica, Jabal Shammar, and rebels in Armenia and Syria

- The anti-Ottoman coalition is defeated in early 1940, but shortly after a second world war breaks out in Europe due to a crisis in Ukraine prompting both Russia and Germany to invade the country. The French Commune joins in as well in defense of Ukraine and the whole web of alliances is triggered again.

- In East Asia, a resurgent Japan takes advantage of the divisions in China to attempt to conquer, but ends up in the mud as the various Chinese faction form a united front. While still stuck in China, Japan decides to take advantage of the war in Europe to seize European (mainly German) colonies in Asia.

- In the US, the country is stuck in civil between various factions since 1937, with the Syndicalists seeming to gain the upper hand, prompting a Canadian intervention.

- The result is that the former entente now finds itself sharing common rivals with the Germans, and they decide to put aside their differences and join the Germans against the Syndicalist Internationale.

- The war thus turns global.

- At first the Germans have the upper hands in the Western front, but they are then pushed back in 1942 and the Internationale reach the Rhine.

- The Ottoman Empire, having so far remained neutral after experiencing its own war, intervenes on behalf of Germany, relieving some much needed pressure off of the Germans.

- Over the next few years, Germany and its allies are able to push back all of their enemies, occupying all of the Internationale powers in Europe, and forcing Russia (after an internal coup) to quit the war and accept a humiliating peace instead.

- Meanwhile, however, the Germans are not able to stop the American syndicalists from winning their civil war and taking over Canada and the Caribbean. Nor are they able to stop Japan from seizing European colonies in Asia or from taking over China.

- The war thus ends in 1947 with German victory in Europe, syndicalist victory in America, and Japanese victory in Asia, and the ground is set for a civil war between three power blocs: Germany’s Europakt, Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere, and the syndicalist Fourth Internationale.

- The Ottoman Empire is unwilling to join Germany’s Europakt and instead joins with their former enemies in Russia, as well as with India (re-unified by a federation of princes headed by Osman Ali Khan), and Brazil, in setting up a non-aligned movement.

The full story write-up (it came out longer than expected):

The post-WK1 (First Weltkrieg) world was one of an uneasy German hegemony. Following its victory in the War, Germany emerged as the supreme master of the European continent, and – following the collapse of the British Empire during the British Revolution – of the world at large. However, this hegemony was never absolute – west of the Kaiserreich, the syndicalist powers of the Third Internationale - not only resented Germany for its victory, but also for its capitalist and reactionary nature, seeking to overturn the entire existing world order through a global revolution; to its east, Russia was still seething from the humiliation of Brest-Litovsk and the subsequent civil war, surrounded by small German satellite states whom it never stopped seeking to re-absorb; to its south and far west, the Entente, the remnants of the French and British empires in exile, longing to return to Europe and re-establish their former dominations; and far to the East, the Japanese Empire never stopped challenging Germany, and constantly attempted to assert itself as the preeminent power of the Orient.

In the Ottoman Empire, the post-WK1 days were not ones of growing domination but of consolidation and reconstruction. The Empire suffered greatly during the war, its army proving to be ineffective without German aid and many of its people resentful of Turkish rule. More than that, the physical destruction suffered in the Empire was massive – in large part the fault of the its own leadership, due to atrocities against the Empire’s non-Turkish and particularly Armenian populations. Despite technically being on the victorious side, and having gained lost territories such as Libya and Kars, the war was largely seen as a failure by much of the politically-active population of the Empire (in great part due to concessions which the Empire still had to give to the Entente in Palestine and Iraq), and the Three Pashas and their CUP leadership were deposed and replaced as soon as the war ended.

In place of the CUP, the 1920’s and 30’s saw the political rise of Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s Ottoman People’s Party (OHF), the new secular and modernizing party within the Empire. Having first been elected as Grand Vizier in 1920’s due to his popularity as the war hero of WK1, Kemal attempted to stabilize the Empire’s dire economic and military situation, and began a program of centralizing, secularizing, and modernizing reforms. The reforms achieved a limited degree of success, but were unpopular with both conservatives and liberals within the Empire, eventually leading to an electoral loss for the OHF in 1931. However, the conservatives and liberals proved themselves far less effective at handling the Empire’s many challenges, and Kemal and the OHF returned to power in 1935.

The global situation began deteriorating for the hegemonic Central Powers in early 1936 – the assassination of Russian premier Kerensky was followed by a nationalist coup led by Boris Savinkov, who proceeded to abolish Russian reparation payments to Germany. Germany of course protested and attempted to use economic means to pressure the New Russian government, but it was not willing to break the peace with Russia for the sake of some cash. The result was that German government bonds quickly and precipitously declines in value, leading to the Black Monday crash of the Berlin stock market, and quickly spiraling into a massive economic crisis engulfing not only Germany, but all of German-dominated Europe.

The forces opposed to Germany’s hegemony, from both the left and right, quickly moved to take advantage of the situation, and the following years appeared as if the German House of Cards may collapse: Civil war in Spain; syndicalist revolution in the Netherlands; nationalist revolution in Norway (led by Vidkun Quisling); the collapse of the United Baltic Duchy and its successor states (except Riga) being swallowed by Savinkov’s Russia; the renewal of the Italian Civil War, with the Syndicalists nearly achieving victory; the Fourth Balkan War and dismantling of Bulgaria’s hegemony over the Balkans by an alliance of Serbia, Romania, and Greece (and with some Ottoman opportunism); a renewed Civil War in China, with Japan quick to take advantage of its massive collapsing neighbor; Russian incursions into Central Asia; colonial revolts in Indochina, the East Indies (controlled by a German-aligned Dutch government-in-exile), and Africa; and of course the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy under the weight of its own non-German minorities.

The Ottoman Empire was, to a certain degree, benefitted by this turn of events: there was some resentment among the Ottoman leadership of the growing dependence on Germany, both militarily and economic, and Black Monday and its aftermath provided an excellent chance to free the Empire of German control. Kemal’s regime proved up to the task, with economic stabilization measures succeeding in preventing a collapse of the Ottoman Empire like that seen in Germany’s satellite states. Beyond that, Kemal even succeeded in regaining some of the Empire’s lost pride when, in early 1937, he took advantage of Bulgaria’s woes against its Serb-Romanian-Greek enemies to seize control of Western Thrace.

These successes gave Kemal to necessary political credit to embark on an ambitious program of modernizing and secularizing political, economic, and military reforms. Opposition from the Empire’s conservatives was significant, but counterproductive: a failed attempt on Kemal’s life in mid-1937 only gave him the necessary excuse to declare martial law, suspend civil liberties, and essentially become a dictator. Once order was restored to the Empire’s streets, Kemal’s first order of business was to enshrine his reforms – by gathering a constitutional convention to rewrite the outdated Ottoman constitution.

The new Ottoman Constitution, inaugurated on December of 1937, was one of the most progressive pieces of law in the non-syndicalist world at the time. It abolished Islam as state religion, enshrined religious and civil liberties, granted universal suffrage including for women, and enshrined the supremacy of elected civil officials (although, the implementation of this part of the constitution was suspended until such time that Kemal saw fit to lift the existing martial law). However, it was also a centralist and authoritarian constitution, establishing a unitary rule that severely limited the autonomy of the Empire’s vilayets and gave supremacy to the Grand Vizier over all other branches of government, thus entrenching OHF rule and effectively enshrining Turkish supremacy over the Empire’s minorities. Thus, the reactions to the new constitution among the Empire’s religious and national minorities were mixed: though it ensured their rights and removed the threats of outright violent forced assimilation, it was not at all an end to Turkification attempts by the government, and certainly their national rights were not recognized.

Regardless however of how the new constitution was received by the Empire’s non-Turks, and despite being a political victory for Kemal, it could not solve the main trouble faced by the Empire at the time: its relations to the Arab world. One can identify four different issues faced by the Ottoman Empire in this field –

Firstly, growing Arab nationalism within the Empire’s own citizens. After the loss of much of the Balkans, Arabs became the main non-Turkish demographic within the Empire, and though a majority of Arabs are Muslim and were therefore loyal to the Caliph, the rise of nationalism among them has served to widen the gap between the Porte and its Arab subjects. Before WK1 this did not seem like a major problem, but following the Arab revolt and the Entente’s promises for Arab statehood at Ottoman expense, this nationalism became an existential threat for the Empire. Though the Arab revolt failed, the sentiments still remained, and while outright agitation for independence from the Empire is illegal (the new constitution permits only limited freedom of speech, with separatism expressly banned) many of the Empire’s Arab citizens were already organizing for the re-establishment of sovereign Arab rule.

Secondly, the status of the ‘emirates’ – these are the self-governing entities within the Empire, chief among them the Emirate of Cyrenaica, the Emirate of Jabal Shammar, and the Imamate of Yemen, which with their autonomous leadership subject to the Sultan-Caliph. Though local rulers exercising autonomy within the Empire were not a new phenomenon, they have always proved to be a thorn at the Porte’s side, and doubly so in the age of Arab nationalism and centralization within the Empire, increasing the tensions between the Porte and the local Emirs who sought to maintain their autonomy.

Third, the status of Palestine and the Zionist movement. Though the Porte never welcomed the immigration of Jewish Zionists into Palestine and always sought to limit it, the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the continued occupation of Palestine by the British at the end of the War had forced the Ottoman government to agree to continued Jewish migration and to recognize at least in part Zionist aspirations. The Porte was reluctant to agree to this, but nevertheless it did, and while Palestine at the time was ruled not directly by the Porte but by an international council, backed by an international gendarmerie, it was still nominally part of the Empire (alongside Sinai and the Suez Canal). Growing Jewish presence in the holy land and the perceived loss of Palestine to the Zionist movement proved to be an additional issue which Arab nationalists would throw at the feet of the Porte – despite the Porte’s own reluctance on the issue.

And finally, the status of Egypt – the largest Arab power – and the control over the Sinai and the Suez Canal. Before WK1, Egypt – including the Sinai and the Canal – were under nominal Ottoman suzerainty, with a local Khedive ruling the country while effective control was held by the British. But with the outbreak of the War these nominal ties were severed by the British, and Egypt made de-jure independent and sovereign. This independence was never officially accepted by the Porte, however with no ability to push into Egypt at the end of the War it had to be de-facto accepted. Instead, the Empire received nominal control over the Sinai, with the Suez Canal managed by the same international council that administers Palestine. This has left neither side satisfied, and both vying to take back control of the region, with the Egyptian conspiring to overthrow Ottoman hegemony entirely.

In addition to Egypt and other Arab powers, the Empire was facing other regional threats: Persia had undergone a socialist revolution in 1936, and now in addition to being the traditional rival to the Ottomans is now an ideological opponent as well; both Georgia and Greece had desires on Ottoman territory inhabited by their respective ethnicities (in particular Greece, which after its victory against Bulgaria hoped it can unify all Greeks under one rule); and other ethnicities within the Empire besides the Arabs – such as Armenians and Kurds – also agitated for independence..

Though the Empire was growing stronger and wealthier under Kemal’s leadership, these various threats only increased over the years, until they eventually came to a head in December of 1938: on December 9, the International Council which administered Palestine voted – under pressure from the Ottoman government and due to increasing unrest from both Arab and Zionist militias – to abolish itself re-integrate the region back into the Empire, including the Sinai, effective within one month. In response, protesting the decision to return the Sinai to the Ottomans, the Egyptian army mobilized, and on December 21, 1938, declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and crossed the Suez Canal. Concluding secret negotiations between Egypt and the Arab Emirates, over the next few weeks the Emir of Cyrenaica and leader of the Senoussi order, the Imam of Yemen, and the Rashidi Emir of Jabal Shammar, all severed ties with the Porte, declared independence, and mobilized their armies against the Ottomans. The Arab leaders called upon the Empire’s Arab subject to join them, and on December 29 atop the Jabal Druz in Syria, local Arab Nationalist leaders declared the formation of the Syrian Republic and called upon all of Greater Syria’s Arabs to join them.

Other powers did not remain idle: in January, the Socialist government of Iran joined the Egyptians and likewise declared war on the Ottoman Empire. A month later, following rejected ultimatums demanding the cession of territory, Greece and Georgia followed suit, as did masses of Armenians in Yerevan who declared independence alongside Syria, and thus so-called ‘Desert War’ began (that is its common name despite having taken place in a variety of landscapes, not only desert).

The Ottoman military quickly mobilized in response and began a march down to Egypt, while holding off attempts by Arab rebels to stall them went on to meet the Egyptians. Within a span of three weeks – led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha personally – pushed back the Egyptian offensive back over the Suez Canal. Attempts to cross the canal were unsuccessful, however, and so the war against Egypt settled into a stalemate.

On paper, the ‘Cairo Pact’ – the informal name for the anti-Ottoman coalition – held the edge in terms of numbers, with around 850k troops total vs. 650k which the Ottomans managed to muster. However, the Ottomans held the advantage in equipment, with a far larger air-force than their rivals as well as a small tank fleet, and the supply system that was partially mobilized. In addition both sides were supported by foreign powers: the Ottomans by the Germans, and the Cairo Pact by the Third Internationale and by Russia.

Considering the limited manpower available to him, and the wide fronts with which he’s faced, Kemal chose a strategy of consolidation and defence on most fronts of the war: Ottoman troops would withdraw to easily defensible lines close to the border, and dig in to expect enemy attacks. Meanwhile, offensives would be limited and carried out mostly against the Rashidi Arabs on the Peninsula using a mobile force backed by armor, as that was deemed to be the weakest link of the anti-Ottoman coalition. This strategy proved a success: offensives from Persia, Greece, and Georgia were all halted shortly after the border, in large parts thanks to Ottoman air superiority and due to the difficult terrain, while renewed attempts by the Egyptians to cross the canal all proved a failure. Against the Rashidis, the Ottoman mobile forces saw relatively quick success, and a majority of their main centers taken with a majority of their forces killed, captures, or scattered, by the end of April. Now, Kemal used newly available forces from the campaign against the Rashidis to subdue the Syrians and Armenians, eliminating both revolts by the end of June.

These successes allowed the Ottoman army to now move to the offensive on most fronts, launching a naval invasion of Derna in Cyrenaica and of the Peloponnese in Greece, hoping to divert Cairo Pact forces away from the existing fronts – which by now have been fortified and reinforced – thus allowing Ottoman forces to break through. Slowly, this worked, and on September 24 1939, Ottoman forces broke into Athens, forcing the Greece’s capitulation. As part of the peace treaty, Greece would be forced to relinquish Crete, and much of its northern territories including Saloniki (Kemal’s birthplace). Further south, Ottoman forces broke through the Yemeni lines and captured San’a and Aden, forcing the Imam of Yemen to flee to Egypt and effectively ending opposition to Ottoman rule on the Arab peninsula. Likewise, the gambit in Cyrenaica worked and the Egyptians had to divert enough forces from the Canal to the west to halt an advance into Egypt that attempts by Ottoman forces to cross it now proved successful, with Cairo itself falling by the end of November. The Egyptian government sued for a truce and attempted to start peace negotiations, but Kemal – emboldened by the recent successes – would accept nothing less than total capitulation and occupation of Egypt, which he eventually received by the end of 1939.

With most of its enemies defeated, only Iran and Georgia remained standing. The attacks into both would prove costly, but Kemal was determined to achieve a total victory over both and remove them as potential rivals to the Empire. It would take until the end of March, while fighting under winter weather in Georgian hills, to force the Georgian government to capitulate, and until the end of April to do the same with Iran (though the Iranian government never officially capitulated, but rather left the country to set a government-in-exile in the Commune of France).

With all its enemies decisively defeated, and in control of virtually the entire middle east, Kemal set out to redraw the borders of the new Ottoman hegemony: Cyrenaica and Yemen would both be annexed and ruled directly from Constantinople as Ottoman vilayets; central Arabia would remain an autonomous emirate, but its ruler replaced with a different branch of the Rashidi dynasty; Egypt and Sudan, it was decided, could not be reintegrated back into the Empire, however they would not remain independent either, but rather restored to the status of Khedivate, recognizing the supremacy of the Sultan-Caliph and placed under its military restriced – and more importantly, with the Suez question settled in favor of the Ottomans; Persia would be forced to relinquish its western territories (Khuzestan, Tabriz, Urmia, and Iranian Kurdistan) and a new regime would be established, with a Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty restored to its throne; Georgia would face no border changes, however it would have to form a new government amenable to the Porte, and allow the stationing of Ottoman troops on its territory.

The Ottoman Empire was now the undisputed master of the Middle East. But this hegemony would not be enjoyed in peace for long: on May 22, 1940, less than a month after the final Ottoman victory of the Desert War, the Second Weltkrieg broke out. Long before Black Monday, there was much discontent within Ukraine, ruled by a German-aligned satellite regime, over the country’s subservience to the German Kaiserreich. That discontent only increased following the Black Monday crash, and syndicalist revolutionary cells began organizing all over the country. Loyalist forces, backed by Germany, were able to keep the lid on the political situation until mid-1937, but at that point figured that the Hetman’s national-conservative regime is doomed, and pressures him to resign and leave the country, and hold new election. These elections were won by the Social Democrats, who embarked on a series of ambitious economic reforms, to the reluctant assent of the Germans. However, as time went on and Ukraine’s reforms grew more and more radical, the rift between Germany and Ukraine only expanded, and with Germany’s economy recovering from Black Monday its tolerance for Ukraine’s Social Democratic government decreased. When Ukraine embarked on a particularly radical set of agrarian reforms, in early 1940, Germany protested that this would be in violation of Mitteleuropa agreements. In response, the Ukrainian government made preparations to openly challenge Germany, and began talks with the Commune of France over Ukraine’s possible assent to the Third Internationale. Germany mobilized in warning, and soon enough France did as well, but the first shot was fired on May 22 when Russian forces crossed the border and invaded Ukraine. Germany, unwilling to let the Russians grab Ukraine, likewise invaded the country, which triggered a French declaration of war in support of Ukraine’s government. The Second Weltkrieg had begun.

Russia under Vozhd (leader) Savinkov was an ultra-nationalist regime bent on restoring the greatness of the Russian Empire, thus erasing the humiliation of WK1. It has been rebuilding its arms industry and military quickly Savinkov took power in 1936, and over the next few years it had absorbed the states of Central Asia, and the breakaway countries of Latvia and Estonia which formed following the collapse of the Baltic Duchy. In its mission to overthrow German hegemony it was aided by Yugoslavia (formed by the Serbs after their victory in the Fourth and Fifth Balkan Wars), Romania (led by the far-right nationalist Iron Guard regime), Norway (under Vidkun Quisling), Lithuania (formerly a German satellite with a German king, it had undergone a nationalist revolution in the early stages of the war), Bulgaria and Albania (both puppet regimes set up by the Yugoslavs and Romanians who occupied said countries following a socialist revolution in defeated Bulgaria).

Germany’s enemies to the west, the Third Internationale, likewise sought to overturn German Hegemony and avenge the defeat of WK1, but in a rather different way. France and Britain, the primary members of the Internationale, had labored for close to two decades on not only constructing a new syndicalist society to overturn the capitalist and imperialist social order, but also to rebuild their armies and navies to match those of Germany. They were joined in this task by the Batavian Commune (set up following the Dutch Revolution of 1937), the Spanish People’s Republic (the successor state to the Kingdom of Spain, which was defeated in 1938 in the civil war), and the Socialist Republic of Italy (still not in full control of all of Italy, but certainly dominant by this point).

Germany itself was joined by Flanders-Wallonia (a German-aligned satellite led by the Kaiser’s son, and which replaced Belgium following WK1), Poland (likewise led by another of the Kaiser’s sons), Czechoslovakia (set up on top the ruins of the Habsburg Empire), Hungary (reeling from the breakup of the Habsburgs, and much reduced in size), the Two Sicilies (still holding on against the Socialists, though on its last legs by this point), Sweden (concerned over Norway’s expansionist goals), Finland, and White Ruthenia. Following the Halifax Conference in September of 1940, the Entente powers (National France in Africa, the British dominions of Canada, the West Indies, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, and the Kingdom of Portugal) put aside their bitterness at Germany’s victory, and – deciding that cooperation with the Germans is the only possible way to reclaim the homes they lost in their countries’ syndicalist revolutions – joined the war on Germany’s side.

The war quickly turned from merely a new great European War, to a true World War: Already at the onset of the War, Canada was involved in the Second American Civil War (starts 1937), attempting to assist any faction that would halt Jack Reed’s syndicalists, who by this point seemed to be gaining the upper hand. After Canada declared war on the Internationale in September 1940, the ACW suddenly became another theater of the European struggle. At the other hand of the world, Japan has been involved in China since 1938, attempting to use the disunited Chinese warlords for its own ends and instead causing the Chinese Federalists, Syndicalists, and Monarchists to all put their differences aside and join a United Front against Japan, unexpectedly bogging Japan down in an inconclusive war. Japan was attempting to create a grand Co-Prosperity Sphere spanning all of East Asia and the Pacific, and viewed China as the first step to achieve such dreams. Already it had alliances with Thailand and the Philippines, promising them territorial expansion and prosperity under a pan-Asian flag. The perfect time to achieve such aspiration seemed to have come following the outbreak of the war in Europe. Germany held Indochina, Malaya, much of the Pacific’s islands, and several concession ports along the coast of China, and a German-aligned Dutch government-in-exile still held the resource-rich Dutch East Indies. Japan joined the war in December of 1940, after months of careful planning, with surprise attacks all over SE Asia and the Pacific.

On the eastern front, German and Russian forces both swept through Ukraine and within less than two months came face-to-face at the Dnieper river, with Russia occupying everything east of the river and Germany occupying everything to the west, Ukraine thus ceasing to exist as an independent country. Russia conducted offensives into White Ruthenia and Finland as well, achieving limited but noteworthy successes, and following the Lithuanian national revolution into East Prussia and Poland, threatening to take Konigsberg. On the western front, French forces were pushing into Flanders-Wallonia and on the verge of taking Brussels, while an armored column drove through the Ardennes and surprised the German rear. This caused a significant degree of panic among the Germans, who scrambled to mount a defense, but French confidence turned into hubris, and their tanks drove far too deep and became cut off from their infantry. The Germans were able to use this golden opportunity to destroy the French armor, inflicting one of the biggest defeats of the early stages of the war. Following this defeat, Germany was able to slowly but surely push the French out of Flanders-Wallonia, and then into France proper, all the while holding back Internationale offensives coming through Batavia. The Germans would reach the gates of Paris in December of 1940, at which point a halt was declared to prepare for a battle over the city. However, preparations were cut short by Japan’s invasion of Indochina and SE Asia.

The German High Command, deciding that a defeat in Asia would be irreversible, decided to divert resources to that theater and defer the offensive on Paris for now. Thus the war in Europe developed into somewhat of a stalemate, which reminded all participants of the horrors of WK1’s trench warfare. For over a year and a half, until the spring of 1942, the frontlines barely moved in the West. There was somewhat more dynamism on the eastern front, but no major offensives on either side. In the Iberian peninsula, the Spanish socialists were able to push the Portuguese into a thin strip of land stretching from Lisbon to Porto, yet were unable to take them. The Japanese were gradually but surely advancing in Indochina and Malaya, but had limited resources to take the islands of SE Asia, and thus by that point had only taken Sulawesi and around half of Borneo, with Sumatra and Java still safe in Dutch hands.

The war in America, however, was far from static. Despite desperate attempts by Canada and by several American factions, the syndicalists seemed to be gaining more and more territory, controlling all of the northern US, Midwest, pacific northwest, Appalachia, and a majority of the South. Only Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas remained under Huey Long’s Union State, and California under the Pacific States command. At this point, Jack Reed made a fateful decision: finishing off the remnants of his American rivals, is far less important than saving the revolution in Europe. Throughout 1941 and early 1942, American troops began streaming into France and Britain, and preparing for a counteroffensive. On June 1942, this offensive began: hundreds of thousands of French, British, Spanish, Italian, and American socialists began pushing into the German lines. Simultaneously, American and British troops landed near Calais, currently under German occupation, threatening the German rear. This proved a success for the syndicalists: by the end of July, German troops were pushed back out of Germany, suffering hundreds of thousands of casualties in the process, and by the end of September American troops had reached the Rhine while British troops liberated Amsterdam, concluding a successful counteroffensive.

Throughout this time, the Ottoman empire was rebuilding and consolidating itself following its victory in the desert war. Kemal died unexpectedly in August 1940, but his successor Ismet Pasha still continued his legacy. At the outbreak of the war, the Empire declared its neutrality, not wishing to be dragged into another war soon after finishing a previous one, despite the Porte’s obvious preference for Germany and its allies. Still, Ismet had no intentions of remaining neutral forever, and as soon as war broke out in Europe, preparations were made to rebuild and modernize the Ottoman army in expectation for war. Following the defeat of Germany in the Internationale’s summer 1942 offensive, it was decided by Ismet that time has come, and that the Ottoman Empire must join the war soon or else risk a Russian and Syndicalist dominated Europe.

The Ottoman Empire officially joined the war in November 1942, after concluding negotiations with Germany that would grant the Ottomans supremacy over the Balkans, Caucasus, and Central Asia in the post-war settlement. Ottoman forces invaded Russia’s Balkan allies, and crossed into the Caucasus and Central Asia, both regions being lightly defended. Initial Ottoman successes were impressive, reaching the Danube by the end of 1942, and taking over Dagestan and Chechnya in the Caucasus and reaching Stavropol and Astrakhan, and in Central Asia much of what used to be Turkestan and the Alash Orda. However, by that they were meeting stiffer resistance, and supply problems exacerbated by the cold weather made further advances impossible. Importantly for the Germans, this had relieved enormous pressure on their eastern front, and allowed them to begin preparations for an anti-Russian offensive.

This they carried out in April 1943, crossing the Dnieper despite heavy casualties, pushing Russia out of Lithuania, and landing (alongside the Ottomans) in Crimea. Over the course of the next several months, Germany and its allies proceeded to take over the rest of Ukraine, liberate all of White Ruthenia, retake Lithuania, advance into the Baltic and liberate Riga, and complete an encirclement of Russian troops in the Caucasus by taking the Kuban in a pincer movement. Russia had suffered a significant defeat and by now had mostly been pushed back to its pre-1938 borders.

Germany has now decided that the Russian threat is mostly contained, and thus all focus needs to be on the western front. A large-scale offensive, supported by Ottoman troops, was planned in the Rhinelands and across the Alps for the Spring of 1944. The balance of power this time was in Germany’s favor. Firstly, since Germany began to win the air war, and the Internationale by that point had conceded air superiority in the Rhinelands and Northern Italy. Secondly, Internationale armies had worn themselves down trying to build on the successes of 1942, instead meeting stiff German resistance which managed to contain all their offensives. Third, a Canadian offensive into New England forced much of the American Expeditionary Force to withdraw from the continent. And fourth, because successful Entente landings in Southern Spain in 1943 forced the Internationale to divert much of its forces to prevent the collapse of the Spanish Socialists. The offensive of Spring 1944 thus proved to be a success, with Flanders-Wallonia and the Rhineland fully liberated by the end of July, at great Internationale losses. Following that, Germany kept advancing into France proper and in November 1944 – for the third time in less than a century – capture Paris. The Communards did not relent, however by that point they had become a spent force. Over the winter of ’44 and ’45, German troops kept marching deeper and deeper into France, and by March of 1945 reached the Pyrenees. The British were evacuating their forces from France and redeploying them to fight in Spain, and the Italians doing likewise to deal with an outpour of German and Czech forces streaming into Northern Italy.

Throughout this time, the eastern front did not remain static, with Germany and allied troops taking Tallin, Smolensk, and Rostov-on-Don, and Ottoman troops capturing Tsaritsyn and Ekaterinburg, over the same time period. However elsewhere in the world Germany and its allies saw mostly defeats: There were no more resources available to divert to the far east, thus German and Dutch forces were forced to remain on the defensive and try to hold on to whatever the Japanese had yet to take, a strategy that ultimately failed to preserve European control in the region, as Japan captured Jakarta (then known as Batavia) on June 1944, thus effectively ending the war in SE Asia (though isolated pockets of German resistance still held out). In America, the Canadians proved to be a spent force, and were being swiftly pushed back, while the Union State and Pacific States both collapsed throughout 1944, thus effectively ending the Second American Civil War with a syndicalist victory.

The Germans and Ottomans kept pushing into Russia throughout 1945 and 1946, and in June 1946 the Russian leadership has had enough of its Vozhd. With Moscow a frontline city and Petrograd besieged, the situation seemed desperate, and a clique of Russian Generals led by Pavel Bermondt-Avalov assassinated Savinkov, launched a coup, and began truce negotiations with the Germans. The German demands were harsh: significant Russian territorial concessions which would, essentially, limit Russia to mostly lands with a Russian ethnic majority, and cutting off Russian access to the Black Sea, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Russia would essentially have to relinquish any dream of being a vast empire, and settle for an existence as another nation-state in a German dominated Europe. In addition, Russia will join Mitteleuropa – thus tying it economically to Germany, and in place of cash reparations physical factories will be relocated from Russia to Germany and its allies to compensate them for the losses of the war. Russia will face severe limitations on its military as well. Still, everything Germany demanded they had already de-facto taken by force, and it was made clear to Bermondt-Avalov that unless these conditions are accepted, Germany will take Moscow and Petrograd, and eliminate the Russian state by force. The Peace of Moscow, signed on July 22 1946, was a humiliating defeat for Russia, but it had also brought it peace at last. For Germany, it allowed it to focus on defeating the Internationale.

Spain had already been occupied by the end of 1945, but Italy and Britain still kept fighting on. With Spain defeated, the Internationale lost access to the Mediterranean, and this allowed Germany and its allies to stage a series of landing throughout the Apennine peninsula, eventually subduing the Italian Socialists by the end of summer, 1946. Thus, continental Europe was now undisputedly under Germany’s hegemony. Only Britain remained to challenge Germany in Europe.

The amphibious invasion of Britain was a complicated, costly affair. Germany and its allies possessed clear aerial and naval superiority, despite American attempts to challenge Germany at sea. Still, by this point the Socialist States of America (as it was now naming itself) had defeated the Canadians, and invaded the Caribbean, thus kicking the Entente out of the Americas, leaving it with plenty of resources to divert for the defense of Britain. But America’s ability to defend Britain was limited not only by distance, but also by its own destruction following years of bloody civil war. It could muster many men for Britain, but Germany and its allies had the whole of Europe, Africa, and the middle east at their disposal, and able to out-produce the SSA despite its still-significant industry. The invasion of Britain – Operation Walrus – began in June of 1947, and saw the first use of nuclear weapons. Despite heavy casualties on both sides, the Internationale forces had nothing comparable to nuclear weapons, which could eliminate entire formations with a single bomb. The war ended before Christmas of that year with the occupation of Britain and restoration of the King (who had by this point fled Canada, and has been residing in French North Africa).

Officially, the war would go on for several more years, concluding with a ceasefire between Japan and Germany in 1948, and the SSA and Germany in 1949, but in practice (barring some u-boat battles) the war was already over: Germany won in Europe; Japan won in Asia; the SSA won in the Americas. The post-war years would be spent by each power consolidating its sphere. The Third Internationale, now defeated, would be replaced by the International Vanguard of Workers’ States, colloquially known as the Fourth Internationale. In Asia, Japan’s victories over the European powers, and its subsequent subjugation of China, meant that now the greater East Asia region was all under Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere. In Europe, Germany consolidated its victories by setting up a mutual defense organization to accompany the economic organization of Mitteleuropa: the Europaische Pakt, or Europakt in short. Even Germany’s former enemies, France and the (now restored) UK join the Europakt, realizing that German hegemony in Europe is a given and that the SSA and Japan are bigger threats. The world thus entered a period of cold war and power struggles between these various blocs, neither one capable or willing to

The Ottoman Empire was reluctant to join the Europakt. Though it was allied with the Germans in both Weltkriegs, it had several objections to joining a German-led defense pact during peacetime: firstly, it never had any interests in the far east, and antagonizing Japan by allying with Germany again seemed counterproductive; but chiefly, at this point the Ottomans were the second most powerful state in Europe, after only Germany itself, with its own sphere of influence in the Balkans, Caucasus, and Central Asia. The Ottomans were more than capable of maintaining that sphere on their own, and had no intention of allowing the Germans a chance to contest their sphere. The Ottoman Empire would remain a part of Mitteleuropa – withdrawing at that point, though it would be a blow to Germany, would be a bigger blow to Ottoman economy – but it would not continue to align itself geo-politically with Germany.

There were other powers in the same position as the Ottomans. Post-Savinkov Russia found itself in a terrible situation. Geopolitically, it was isolated and surrounded by its former enemies. Economically and demographically, as well, it was ruined from years of war. The Ottomans were the first to take advantage of the situation. Though they were veteran rivals, and fought each other recently in WK2, both had a mutual interest in checking German power in Europe. Additionally, Russia desperately needed new investments and the Porte was glad to take advantage of their need. India, too, was interested in fending off foreign power blocs. During the interwar years, the Indian subcontinent was divided between the Dominion – the reformed remnants of the British Raj retaining control over the northwest and centered around the Indus valley, the Commune – an attempted syndicalist revolution controlling the north and east of the subcontinent, and the Princely Federation – a collection of local princes, centered in the Deccan, who rejected both former rulers and desired an independent, federal, and conservative India. In the years preceding WK2, all three fought wars against each other, which result in a Princely Federation victory. The Federation thus renamed itself as the Indian Empire, with its head – the Prince of Hyderabad Osman Ali Khan – as Emperor of India. The Indian Empire sat out the Second Weltkrieg as a neutral power, focusing on rebuilding a united Indian nation and profiting off of trade with all sides. After the war, India found itself pressured by Japan to join the Co-Prosperity Sphere, however the most populous country on earth had no desire to play second fiddle to anyone. The Emperor’s son and heir was already married to an Ottoman princess, and so cementing the alliance between India and the Ottomans seemed like a logical next step. The trifecta of the Ottomans, Russia and India was joined by Brazil, who found itself in a similar position to India in relation to the SSA in the Americas. In 1949, these four power, as well as countries within their spheres of influence, joined together to form the Non-Aligned Movement, pledging no support for any of the power blocs, and officially open to diplomatic relations and trade with all of them.

Thus, the cold war began with three power blocs, and an additional fourth one that openly rejected the idea of a cold war. The world in 1949 was officially at peace, but the war would continue not only as a power struggle between the various blocs, but also in practice as insurgencies ravaged several countries: Both Japan and the SSA were funding anti-Colonial revolts in Africa, and syndicalist resistance movement in formerly-syndicalist European states; Germany and the UK, in return, were still supporting the remnants of Dominion forces waging an insurgency in Canadian forests, as well as right-wing militias throughout the Americas; and both Germany and the SSA were each funding their own anti-Japanese guerillas in China, which would forever prevent Japan’s puppet regime in Nanjing from establishing full control over the countryside.

In the Ottoman Empire, the post-WK1 days were not ones of growing domination but of consolidation and reconstruction. The Empire suffered greatly during the war, its army proving to be ineffective without German aid and many of its people resentful of Turkish rule. More than that, the physical destruction suffered in the Empire was massive – in large part the fault of the its own leadership, due to atrocities against the Empire’s non-Turkish and particularly Armenian populations. Despite technically being on the victorious side, and having gained lost territories such as Libya and Kars, the war was largely seen as a failure by much of the politically-active population of the Empire (in great part due to concessions which the Empire still had to give to the Entente in Palestine and Iraq), and the Three Pashas and their CUP leadership were deposed and replaced as soon as the war ended.

In place of the CUP, the 1920’s and 30’s saw the political rise of Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s Ottoman People’s Party (OHF), the new secular and modernizing party within the Empire. Having first been elected as Grand Vizier in 1920’s due to his popularity as the war hero of WK1, Kemal attempted to stabilize the Empire’s dire economic and military situation, and began a program of centralizing, secularizing, and modernizing reforms. The reforms achieved a limited degree of success, but were unpopular with both conservatives and liberals within the Empire, eventually leading to an electoral loss for the OHF in 1931. However, the conservatives and liberals proved themselves far less effective at handling the Empire’s many challenges, and Kemal and the OHF returned to power in 1935.

The global situation began deteriorating for the hegemonic Central Powers in early 1936 – the assassination of Russian premier Kerensky was followed by a nationalist coup led by Boris Savinkov, who proceeded to abolish Russian reparation payments to Germany. Germany of course protested and attempted to use economic means to pressure the New Russian government, but it was not willing to break the peace with Russia for the sake of some cash. The result was that German government bonds quickly and precipitously declines in value, leading to the Black Monday crash of the Berlin stock market, and quickly spiraling into a massive economic crisis engulfing not only Germany, but all of German-dominated Europe.

The forces opposed to Germany’s hegemony, from both the left and right, quickly moved to take advantage of the situation, and the following years appeared as if the German House of Cards may collapse: Civil war in Spain; syndicalist revolution in the Netherlands; nationalist revolution in Norway (led by Vidkun Quisling); the collapse of the United Baltic Duchy and its successor states (except Riga) being swallowed by Savinkov’s Russia; the renewal of the Italian Civil War, with the Syndicalists nearly achieving victory; the Fourth Balkan War and dismantling of Bulgaria’s hegemony over the Balkans by an alliance of Serbia, Romania, and Greece (and with some Ottoman opportunism); a renewed Civil War in China, with Japan quick to take advantage of its massive collapsing neighbor; Russian incursions into Central Asia; colonial revolts in Indochina, the East Indies (controlled by a German-aligned Dutch government-in-exile), and Africa; and of course the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy under the weight of its own non-German minorities.

The Ottoman Empire was, to a certain degree, benefitted by this turn of events: there was some resentment among the Ottoman leadership of the growing dependence on Germany, both militarily and economic, and Black Monday and its aftermath provided an excellent chance to free the Empire of German control. Kemal’s regime proved up to the task, with economic stabilization measures succeeding in preventing a collapse of the Ottoman Empire like that seen in Germany’s satellite states. Beyond that, Kemal even succeeded in regaining some of the Empire’s lost pride when, in early 1937, he took advantage of Bulgaria’s woes against its Serb-Romanian-Greek enemies to seize control of Western Thrace.

These successes gave Kemal to necessary political credit to embark on an ambitious program of modernizing and secularizing political, economic, and military reforms. Opposition from the Empire’s conservatives was significant, but counterproductive: a failed attempt on Kemal’s life in mid-1937 only gave him the necessary excuse to declare martial law, suspend civil liberties, and essentially become a dictator. Once order was restored to the Empire’s streets, Kemal’s first order of business was to enshrine his reforms – by gathering a constitutional convention to rewrite the outdated Ottoman constitution.

The new Ottoman Constitution, inaugurated on December of 1937, was one of the most progressive pieces of law in the non-syndicalist world at the time. It abolished Islam as state religion, enshrined religious and civil liberties, granted universal suffrage including for women, and enshrined the supremacy of elected civil officials (although, the implementation of this part of the constitution was suspended until such time that Kemal saw fit to lift the existing martial law). However, it was also a centralist and authoritarian constitution, establishing a unitary rule that severely limited the autonomy of the Empire’s vilayets and gave supremacy to the Grand Vizier over all other branches of government, thus entrenching OHF rule and effectively enshrining Turkish supremacy over the Empire’s minorities. Thus, the reactions to the new constitution among the Empire’s religious and national minorities were mixed: though it ensured their rights and removed the threats of outright violent forced assimilation, it was not at all an end to Turkification attempts by the government, and certainly their national rights were not recognized.

Regardless however of how the new constitution was received by the Empire’s non-Turks, and despite being a political victory for Kemal, it could not solve the main trouble faced by the Empire at the time: its relations to the Arab world. One can identify four different issues faced by the Ottoman Empire in this field –

Firstly, growing Arab nationalism within the Empire’s own citizens. After the loss of much of the Balkans, Arabs became the main non-Turkish demographic within the Empire, and though a majority of Arabs are Muslim and were therefore loyal to the Caliph, the rise of nationalism among them has served to widen the gap between the Porte and its Arab subjects. Before WK1 this did not seem like a major problem, but following the Arab revolt and the Entente’s promises for Arab statehood at Ottoman expense, this nationalism became an existential threat for the Empire. Though the Arab revolt failed, the sentiments still remained, and while outright agitation for independence from the Empire is illegal (the new constitution permits only limited freedom of speech, with separatism expressly banned) many of the Empire’s Arab citizens were already organizing for the re-establishment of sovereign Arab rule.

Secondly, the status of the ‘emirates’ – these are the self-governing entities within the Empire, chief among them the Emirate of Cyrenaica, the Emirate of Jabal Shammar, and the Imamate of Yemen, which with their autonomous leadership subject to the Sultan-Caliph. Though local rulers exercising autonomy within the Empire were not a new phenomenon, they have always proved to be a thorn at the Porte’s side, and doubly so in the age of Arab nationalism and centralization within the Empire, increasing the tensions between the Porte and the local Emirs who sought to maintain their autonomy.

Third, the status of Palestine and the Zionist movement. Though the Porte never welcomed the immigration of Jewish Zionists into Palestine and always sought to limit it, the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the continued occupation of Palestine by the British at the end of the War had forced the Ottoman government to agree to continued Jewish migration and to recognize at least in part Zionist aspirations. The Porte was reluctant to agree to this, but nevertheless it did, and while Palestine at the time was ruled not directly by the Porte but by an international council, backed by an international gendarmerie, it was still nominally part of the Empire (alongside Sinai and the Suez Canal). Growing Jewish presence in the holy land and the perceived loss of Palestine to the Zionist movement proved to be an additional issue which Arab nationalists would throw at the feet of the Porte – despite the Porte’s own reluctance on the issue.

And finally, the status of Egypt – the largest Arab power – and the control over the Sinai and the Suez Canal. Before WK1, Egypt – including the Sinai and the Canal – were under nominal Ottoman suzerainty, with a local Khedive ruling the country while effective control was held by the British. But with the outbreak of the War these nominal ties were severed by the British, and Egypt made de-jure independent and sovereign. This independence was never officially accepted by the Porte, however with no ability to push into Egypt at the end of the War it had to be de-facto accepted. Instead, the Empire received nominal control over the Sinai, with the Suez Canal managed by the same international council that administers Palestine. This has left neither side satisfied, and both vying to take back control of the region, with the Egyptian conspiring to overthrow Ottoman hegemony entirely.

In addition to Egypt and other Arab powers, the Empire was facing other regional threats: Persia had undergone a socialist revolution in 1936, and now in addition to being the traditional rival to the Ottomans is now an ideological opponent as well; both Georgia and Greece had desires on Ottoman territory inhabited by their respective ethnicities (in particular Greece, which after its victory against Bulgaria hoped it can unify all Greeks under one rule); and other ethnicities within the Empire besides the Arabs – such as Armenians and Kurds – also agitated for independence..

Though the Empire was growing stronger and wealthier under Kemal’s leadership, these various threats only increased over the years, until they eventually came to a head in December of 1938: on December 9, the International Council which administered Palestine voted – under pressure from the Ottoman government and due to increasing unrest from both Arab and Zionist militias – to abolish itself re-integrate the region back into the Empire, including the Sinai, effective within one month. In response, protesting the decision to return the Sinai to the Ottomans, the Egyptian army mobilized, and on December 21, 1938, declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and crossed the Suez Canal. Concluding secret negotiations between Egypt and the Arab Emirates, over the next few weeks the Emir of Cyrenaica and leader of the Senoussi order, the Imam of Yemen, and the Rashidi Emir of Jabal Shammar, all severed ties with the Porte, declared independence, and mobilized their armies against the Ottomans. The Arab leaders called upon the Empire’s Arab subject to join them, and on December 29 atop the Jabal Druz in Syria, local Arab Nationalist leaders declared the formation of the Syrian Republic and called upon all of Greater Syria’s Arabs to join them.

Other powers did not remain idle: in January, the Socialist government of Iran joined the Egyptians and likewise declared war on the Ottoman Empire. A month later, following rejected ultimatums demanding the cession of territory, Greece and Georgia followed suit, as did masses of Armenians in Yerevan who declared independence alongside Syria, and thus so-called ‘Desert War’ began (that is its common name despite having taken place in a variety of landscapes, not only desert).

The Ottoman military quickly mobilized in response and began a march down to Egypt, while holding off attempts by Arab rebels to stall them went on to meet the Egyptians. Within a span of three weeks – led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha personally – pushed back the Egyptian offensive back over the Suez Canal. Attempts to cross the canal were unsuccessful, however, and so the war against Egypt settled into a stalemate.

On paper, the ‘Cairo Pact’ – the informal name for the anti-Ottoman coalition – held the edge in terms of numbers, with around 850k troops total vs. 650k which the Ottomans managed to muster. However, the Ottomans held the advantage in equipment, with a far larger air-force than their rivals as well as a small tank fleet, and the supply system that was partially mobilized. In addition both sides were supported by foreign powers: the Ottomans by the Germans, and the Cairo Pact by the Third Internationale and by Russia.

Considering the limited manpower available to him, and the wide fronts with which he’s faced, Kemal chose a strategy of consolidation and defence on most fronts of the war: Ottoman troops would withdraw to easily defensible lines close to the border, and dig in to expect enemy attacks. Meanwhile, offensives would be limited and carried out mostly against the Rashidi Arabs on the Peninsula using a mobile force backed by armor, as that was deemed to be the weakest link of the anti-Ottoman coalition. This strategy proved a success: offensives from Persia, Greece, and Georgia were all halted shortly after the border, in large parts thanks to Ottoman air superiority and due to the difficult terrain, while renewed attempts by the Egyptians to cross the canal all proved a failure. Against the Rashidis, the Ottoman mobile forces saw relatively quick success, and a majority of their main centers taken with a majority of their forces killed, captures, or scattered, by the end of April. Now, Kemal used newly available forces from the campaign against the Rashidis to subdue the Syrians and Armenians, eliminating both revolts by the end of June.

These successes allowed the Ottoman army to now move to the offensive on most fronts, launching a naval invasion of Derna in Cyrenaica and of the Peloponnese in Greece, hoping to divert Cairo Pact forces away from the existing fronts – which by now have been fortified and reinforced – thus allowing Ottoman forces to break through. Slowly, this worked, and on September 24 1939, Ottoman forces broke into Athens, forcing the Greece’s capitulation. As part of the peace treaty, Greece would be forced to relinquish Crete, and much of its northern territories including Saloniki (Kemal’s birthplace). Further south, Ottoman forces broke through the Yemeni lines and captured San’a and Aden, forcing the Imam of Yemen to flee to Egypt and effectively ending opposition to Ottoman rule on the Arab peninsula. Likewise, the gambit in Cyrenaica worked and the Egyptians had to divert enough forces from the Canal to the west to halt an advance into Egypt that attempts by Ottoman forces to cross it now proved successful, with Cairo itself falling by the end of November. The Egyptian government sued for a truce and attempted to start peace negotiations, but Kemal – emboldened by the recent successes – would accept nothing less than total capitulation and occupation of Egypt, which he eventually received by the end of 1939.

With most of its enemies defeated, only Iran and Georgia remained standing. The attacks into both would prove costly, but Kemal was determined to achieve a total victory over both and remove them as potential rivals to the Empire. It would take until the end of March, while fighting under winter weather in Georgian hills, to force the Georgian government to capitulate, and until the end of April to do the same with Iran (though the Iranian government never officially capitulated, but rather left the country to set a government-in-exile in the Commune of France).

With all its enemies decisively defeated, and in control of virtually the entire middle east, Kemal set out to redraw the borders of the new Ottoman hegemony: Cyrenaica and Yemen would both be annexed and ruled directly from Constantinople as Ottoman vilayets; central Arabia would remain an autonomous emirate, but its ruler replaced with a different branch of the Rashidi dynasty; Egypt and Sudan, it was decided, could not be reintegrated back into the Empire, however they would not remain independent either, but rather restored to the status of Khedivate, recognizing the supremacy of the Sultan-Caliph and placed under its military restriced – and more importantly, with the Suez question settled in favor of the Ottomans; Persia would be forced to relinquish its western territories (Khuzestan, Tabriz, Urmia, and Iranian Kurdistan) and a new regime would be established, with a Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty restored to its throne; Georgia would face no border changes, however it would have to form a new government amenable to the Porte, and allow the stationing of Ottoman troops on its territory.

The Ottoman Empire was now the undisputed master of the Middle East. But this hegemony would not be enjoyed in peace for long: on May 22, 1940, less than a month after the final Ottoman victory of the Desert War, the Second Weltkrieg broke out. Long before Black Monday, there was much discontent within Ukraine, ruled by a German-aligned satellite regime, over the country’s subservience to the German Kaiserreich. That discontent only increased following the Black Monday crash, and syndicalist revolutionary cells began organizing all over the country. Loyalist forces, backed by Germany, were able to keep the lid on the political situation until mid-1937, but at that point figured that the Hetman’s national-conservative regime is doomed, and pressures him to resign and leave the country, and hold new election. These elections were won by the Social Democrats, who embarked on a series of ambitious economic reforms, to the reluctant assent of the Germans. However, as time went on and Ukraine’s reforms grew more and more radical, the rift between Germany and Ukraine only expanded, and with Germany’s economy recovering from Black Monday its tolerance for Ukraine’s Social Democratic government decreased. When Ukraine embarked on a particularly radical set of agrarian reforms, in early 1940, Germany protested that this would be in violation of Mitteleuropa agreements. In response, the Ukrainian government made preparations to openly challenge Germany, and began talks with the Commune of France over Ukraine’s possible assent to the Third Internationale. Germany mobilized in warning, and soon enough France did as well, but the first shot was fired on May 22 when Russian forces crossed the border and invaded Ukraine. Germany, unwilling to let the Russians grab Ukraine, likewise invaded the country, which triggered a French declaration of war in support of Ukraine’s government. The Second Weltkrieg had begun.

Russia under Vozhd (leader) Savinkov was an ultra-nationalist regime bent on restoring the greatness of the Russian Empire, thus erasing the humiliation of WK1. It has been rebuilding its arms industry and military quickly Savinkov took power in 1936, and over the next few years it had absorbed the states of Central Asia, and the breakaway countries of Latvia and Estonia which formed following the collapse of the Baltic Duchy. In its mission to overthrow German hegemony it was aided by Yugoslavia (formed by the Serbs after their victory in the Fourth and Fifth Balkan Wars), Romania (led by the far-right nationalist Iron Guard regime), Norway (under Vidkun Quisling), Lithuania (formerly a German satellite with a German king, it had undergone a nationalist revolution in the early stages of the war), Bulgaria and Albania (both puppet regimes set up by the Yugoslavs and Romanians who occupied said countries following a socialist revolution in defeated Bulgaria).

Germany’s enemies to the west, the Third Internationale, likewise sought to overturn German Hegemony and avenge the defeat of WK1, but in a rather different way. France and Britain, the primary members of the Internationale, had labored for close to two decades on not only constructing a new syndicalist society to overturn the capitalist and imperialist social order, but also to rebuild their armies and navies to match those of Germany. They were joined in this task by the Batavian Commune (set up following the Dutch Revolution of 1937), the Spanish People’s Republic (the successor state to the Kingdom of Spain, which was defeated in 1938 in the civil war), and the Socialist Republic of Italy (still not in full control of all of Italy, but certainly dominant by this point).

Germany itself was joined by Flanders-Wallonia (a German-aligned satellite led by the Kaiser’s son, and which replaced Belgium following WK1), Poland (likewise led by another of the Kaiser’s sons), Czechoslovakia (set up on top the ruins of the Habsburg Empire), Hungary (reeling from the breakup of the Habsburgs, and much reduced in size), the Two Sicilies (still holding on against the Socialists, though on its last legs by this point), Sweden (concerned over Norway’s expansionist goals), Finland, and White Ruthenia. Following the Halifax Conference in September of 1940, the Entente powers (National France in Africa, the British dominions of Canada, the West Indies, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, and the Kingdom of Portugal) put aside their bitterness at Germany’s victory, and – deciding that cooperation with the Germans is the only possible way to reclaim the homes they lost in their countries’ syndicalist revolutions – joined the war on Germany’s side.