Burton K Wheeler

Moderator

A scenario from the Internet:

https://navy-matters.blogspot.com/2019/04/japanese-invasion-of-pearl-harbor.html

All credit belongs to ComNavOps. I copied the post in its entirety for ease of discussion, but please check out the author's blog.

Here’s another ‘what if’ version of history: what if the Japanese had immediately invaded Hawaii after attacking Pearl Harbor? How would the war have progressed from that point? Let’s see.

Note: Credit for this idea goes to blog reader ‘Purple Calico’ who suggested the topic during the recent open post discussion. (3)

The initial premise is that the attack on Pearl Harbor and all the related events happened exactly as history records except that the Japanese fleet contained an invasion force and the Japanese continued on to Pearl Harbor rather than turning away.

To review, the Japanese strike fleet consisted of 6 aircraft carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku) with well over 400 aircraft, protected by 2 battleships, 3 cruisers, and 9 destroyers (all actual). Accompanying the strike were 8 tankers (actual) which would prove crucial in our alter-history by sustaining the fleets while the island was being secured.

In addition, 23 fleet submarines (actual, 4) were assigned to provide containment around Pearl Harbor to prevent any surviving US ships from escaping to open waters (1) and screening for the strike and invasion fleets. A third were assigned to screen the fleet to the east of Oahu, another third capped the Pearl Harbor channel to the south, and the remaining third patrolled the waters to the west of Oahu.

The alter-historical addition to the Japanese strike fleet is an invasion force consisted of an armored division with 10,000 men and 270 tanks plus dozens of artillery and anti-tank guns plus an infantry division of almost 25,000 men supported by several dozen artillery guns, all loaded on dozens of transport vessels.

The attack on Pearl Harbor came from the north with the 1st wave launching around 220 miles north of Pearl Harbor. The strike fleet continued to sail east and launched the 2nd wave from the northeast.

The first two attack waves succeeded in sinking or damaging nearly all the battleships and cruisers and eliminated effective aerial resistance. Of the 402 American aircraft in Hawaii, 188 were destroyed and 159 damaged, 155 of them on the ground (actual).

Note: An outstanding map of Pearl Harbor ships and facilities at the moment of attack can be found on the National Geographic website. (2)

What follows is a descriptive alter-historical summary of events beginning immediately after the 2nd assault wave of Japanese aircraft.

A 3rd wave was launched from east of Oahu and focused on the ten or so destroyers which had been largely untouched in the first two strikes and any remaining aircraft on the ground. By the time the 3rd wave was finished, there were very few undamaged ships in Pearl Harbor.

The strike fleet continued sailing in a clockwise circle around Oahu, escorting the transport vessels. The land assault would be focused on the militarized island of Oahu which contained the Pearl Harbor naval base, Marine barracks, and multiple air fields. The remaining Hawaiian islands did not need to be occupied. This allowed the Japanese to concentrate their resources on a single small island only 20 miles or so across.

With no American air power to worry about, the two Japanese battleships raced ahead of the rest of the invasion and strike fleets and entered the Pearl Harbor channel at dusk. Their mission was to destroy any remaining ships, bombard the facilities that the Japanese didn’t need to occupy and reuse, and to distract from the assault force that began their landings at the same time. There was risk with attempting an evening landing rather than waiting for dawn but it was felt that the risk was worth it to maintain the shock and confusion that the reeling Americans were under.

As it turned out, the Japanese battleships were hugely successful with the Americans firing on their own ships as much as the Japanese did due to the darkness, confusion, and panic. With reports of Japanese troop landings, and the evidence of Japanese ships in the harbor, American troops began firing on their own ground forces as they were totally untrained and unprepared for night combat and had not trained for friendly forces identification. By morning, the Japanese ground forces were well established and by the end of the day on the 8th were in control of the Pearl Harbor facilities.

Japanese Forces Landing on Oahu

The USS Enterprise, returning from delivering Wildcats to Wake Island, was 215 miles west of Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacks began. Several of Enterprise’s SBDs had flown ahead to Pearl and were shot down by friendly fire. Enterprise spent the day of the 7thsearching for the Japanese strike fleet but found nothing since the Japanese fleets were on the opposite side of Oahu. As reports of Japanese invasion forces reached Enterprise, Admiral Halsey headed southeast and began to assemble an aerial strike force. Unfortunately, that brought Enterprise into the teeth of the Japanese submarine screen and a Japanese submarine found her and put three torpedoes into the ship. Over the next several hours, a second Japanese submarine was able to approach and hit Enterprise with two more torpedoes. Her fate was sealed. Enterprise was a blazing wreck and eventually sank during the night of the 8th.

Enterprise Torpedoed and Sinking

Meanwhile, Lexington, which had been on a mission to deliver planes to Midway, found herself caught halfway between Midway and Pearl Harbor and with her escorts low on fuel due to previous refueling difficulties (actual). With Enterprise sunk, the Japanese dispatched four carriers to search for Lexington and, on the 12th, found her, thus setting the stage for the first carrier battle where the opposing ships never saw each other. Both sides launched nearly simultaneous attacks. Lexington, with only a single air group which included over a dozen older Brewster Buffalos, was unable to fight off the Japanese attack and suffered two bomb hits, two torpedoes, and a damaged Japanese plane that dove into the carrier. Lexington’s strike, facing the defensive CAP of four carriers, managed to score two bomb hits on the Kaga which damaged the carrier enough to curtail flight operations but did not sink it. Both sides recovered their strikes but the Japanese, with greater numbers, were able to launch a second, standby, strike before Lexington could effect repairs sufficient to assemble another strike. The second strike finished off the Lexington.

This left Saratoga, which was training her air group in San Diego, as the only US carrier in the Pacific. Yorktown, Hornet, and Ranger and Wasp were training in Norfolk. Ranger was considered unsuited for the Pacific and was destined for Atlantic and European operations. It would be many weeks before Yorktown, Hornet, and Wasp could be moved to the Pacific and the Japanese used that time to secure Pearl Harbor and set it up as their forward base. Japanese army aircraft fighters were ferried to the island along with long range patrol planes and bombers.

One of the major benefits for the Japanese in seizing Pearl Harbor was the presence of the drydocks which they had wisely and carefully avoided damaging in the initial attacks and which were captured largely intact and quickly returned to service. Damaged Japanese ships which might otherwise have had to return to Japan for repair, were able to be serviced locally, at Pearl Harbor, and returned to combat much quicker. This was significant as even the base at Truk lacked significant repair facilities.

Fall of Wake – On 11-Dec-1941, Wake defenders fought off the first Japanese landing attempt, sinking two Japanese destroyers with coastal defense guns and Wildcat aircraft. A second assault initiated shortly after midnight on 23-Dec-1941 succeeded and the island fell later that same day.

Seizure of Tulagi and Port Moresby (Coral Sea) – The Japanese planned to seize Tulagi and Port Moresby in operations that began in April 1942. The Americans were able to intercept and decipher Japanese signals and knew the general location and timing of the operations. Having lost Pearl Harbor, the threat to Australia as a forward base was considered strategically vital and an operation to intercept the Japanese in or around the Coral Sea was initiated. The carrier Yorktown, recently arrived in the Pacific, was patrolling in the area to the west of Australia and Saratoga was dispatched from San Diego to join her and meet the Japanese invasion fleet. The Japanese sent the Carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, and Shoho to screen the invasion forces from the north and a surface force centered around the battleship Yamato approached from the northeast from Pearl Harbor. Despite the efforts of their respective scout aircraft, the two sides stumbled across each other during the night of 6-May with the Yamato group sighting the Yorktown and Saratoga which had joined up the previous day. The Japanese and American destroyer screens made contact and exchanged fire in a wild night battle which the Japanese cruisers and the Yamato quickly jumped into. When word came that a Japanese battleship was part of the attack, the American carriers conducted an impromptu and untrained-for night launch and attack. Despite the darkness and their lack of training, the untrained flyers succeeded in hitting Yamato with one torpedo and a cruiser was hit with two bombs. Unfortunately, in the darkness, confusion, and co-mingling of the ships, the flyers also torpedoed and sank a US destroyer. As dawn approached, and fearing further aerial attacks, the Japanese broke off the attack and steamed away.

Yorktown and Saratoga Night Attack on Yamato

However, with the US carrier force now located, the Japanese carriers launched a heavy dawn attack which caught the US carriers and their exhausted pilots unprepared. Saratoga was heavily damaged by multiple torpedoes and bombs and Yorktown suffered two bomb hits. When the attack ended, Yorktown, whose dawn scouting planes had located the Japanese carriers, was still able to conduct flight operations and launched a counterattack which caught the Japanese carriers refueling and rearming their aircraft. Shoho was sunk and Shokaku was heavily damaged.

After recovering her aircraft, Yorktown broke off the engagement and retired to the southeast and back to San Diego for repairs. Saratoga was taken under tow but the Yamato group, reversing course and returning to the area to mop up, fell upon the carrier and sank it with gunfire.

The Battle of the Coral Sea, as it came to be known, was a tactical draw but because the US was unable to stop the Japanese invasion fleet which still had sizable carrier and surface forces in the area to provide protection, the Japanese were able to complete the seizure of Port Moresby which was then used as a staging area to threaten Australia directly.

With the loss of Saratoga, only the Hornet, Wasp, and damaged Yorktown remained from the pre-war US carrier force.

The Japanese then seized Midway, costing the US the valuable PBY Catalina patrol and scouting base. Despite having knowledge of the Japanese intentions via signals analysis, the US simply didn’t have the naval strength to contest the Japanese invasion.

The US was now forced to operate from Australia, the Aleutians, and San Diego. None of these options was desirable although Australia was, at least, near the action due to the Japanese seizures. US efforts for the next several months centered on reinforcing Australia and beefing up its defenses. If Australia fell, the US would be effectively ejected from the Pacific theatre.

Taking a cue from the Germans, the Japanese began conducting aggressive Australian convoy interdiction using submarines based out of Pearl Harbor. The Battle of the Pacific, mirroring the Battle of the Atlantic, became a logistic supply contest with the US attempting to reinforce Australia and the Japanese attempting to cut the supply line.

The Japanese, having essentially secured the Pacific now focused on a holding strategy in an attempt to force the US into a negotiated peace. The Japanese believed that the US, already occupied with the war in Europe, would grow weary of fighting a difficult war in the Pacific and lacked the stomach for the casualties such an endeavor would entail.

To that end, in late 1942 the Japanese dispatched a strike force of carriers and battleships to the west coast of the US to conduct bombardment raids which, it was hoped, would further discourage a demoralized populace and force the US to negotiate. The strike force arrived off the coast of Washington and began moving south, bombarding cities and targets of opportunity as they went. The intent was to inflict some casualties and instill fear in the populace rather than achieve any specific military success. After 24 hours of nearly continuous bombardment, the group turned away and retired to avoid the inevitable surge of US naval forces to the area from San Francisco and San Diego.

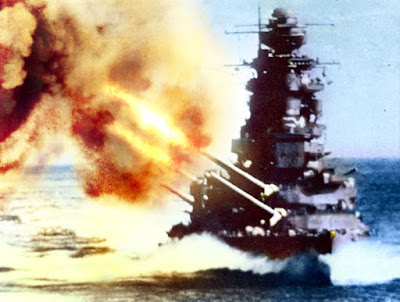

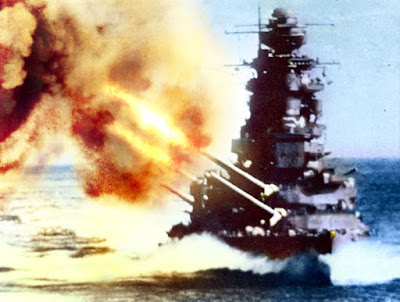

Japanese Battleship Bombarding Washington Coast

While the operation was executed flawlessly the reaction of the American people was a surge of anger, defiance, and cries for revenge and retaliation. As a result of the raid, US determination to defeat Japan was greater than ever, much to the disbelief of the Japanese strategists.

There was little doubt that the US needed to recapture Pearl Harbor to support the war with Japan. However, by this time, Japan had had a year to fortify the base and seizing it by a direct assault with the closest support being the US west coast was not immediately feasible. Instead, US military strategists opted to seize Midway atoll first and then use Midway to screen and support a subsequent assault against Pearl Harbor. An invasion force consisting of Maj. Gen. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division and supported by the carriers Yorktown, Hornet, Wasp, and the newly arrived Essex along with RAdm. Willis ‘Ching’ Lee’s battleship group of North Carolina, Washington, Indiana, and South Dakota was assembled in the Aleutians at Dutch Harbor and sailed for Midway in May 1943.

As the force approached Midway from the north, the carriers broke off and circled to the east to take a position to the southeast of Midway, somewhat between it and Pearl Harbor. As expected, the battleships and troop transports were spotted by long range patrol planes from Midway. The Japanese surged four carriers and their escorts, including the battleships Yamato, the newly arrived Musashi, and the older battleships Nagato, Mutsu, and Fuso from Pearl Harbor to intercept the American force.

The US transport fleet hung back while the battleship group and its escorts took the lead. As the US fleet approached Midway, the Japanese launched two aerial strikes of high level bombers from Midway. The concentrated anti-aircraft fire of the US battleships and escorts, combined with the inherent inaccuracy of high level bombing resulted in only two hits: one bomb hit the South Dakota resulting in only minor damage and a more serious hit on a cruiser which was forced to retire northward.

Having yet to spot any US carriers, the Japanese saw the chance to engage the US battleships in the long-desired battle line confrontation. The Japanese battleships sprinted ahead to meet the US battleships.

Japanese Battle Line Steaming To Meet US Battleships

Shortly after, scout planes from the Japanese and US carrier forces located each other, roughly simultaneously and both sides launched strikes at the other’s carriers. Each realized that the carriers were the priority targets and that their respective battleship forces would have to take care of themselves without the benefit of air cover.

The Japanese strike aircraft reached the American carriers first and managed to penetrate the carriers CAP and escort screen to put two torpedoes into Hornet and one into Wasp. Essex and Wasp were each hit by two bombs. The US strike failed to achieve any torpedo hits but put three bombs into Akagi, and two into Soryu. At the end of the exchange, Wasp was left ablaze and drifting while Essex worked frantically to control internal fires and patch her flight deck. Hornet was slowed due to flooding but otherwise operational. On the Japanese side, Japanese damage control measures proved to be less effective than US efforts and Akagi was left a wreck and Soryu was badly damaged but working to regain operational ability.

A brief pause ensued while both sides worked on damage control and refueled and rearmed for a follow up strike.

Meanwhile, to the northwest, the US battleships, using their SOC Seagull and OS2U Kingfisher scout planes, were aware of the approaching Japanese battleship group and moved to meet them.

While the two forces sailed towards each other, the carriers launched their second strikes. This time, the US carriers were able to turn their strike groups around a bit faster than the Japanese and struck first. The pilots bypassed the blazing Akagi and concentrated on Kaga and Hiryu, managing to put a single torpedo into Kaga along with three bombs. Hiryu suffered one bomb hit and two near misses. The Japanese strike found Hornet and Essex and put three torpedoes into Hornet along with two bombs and Essex was hit by another bomb and a torpedo. Both strikes returned to their carriers and both carrier groups broke off from the engagement, too damaged to continue.

By this time, the approaching battleship groups were entering into range of each other. This turned into the classic battle line engagement with the two groups turning to face each other. Thanks to the Yamato and Musashi the Japanese battleships held an initial range advantage and opened fire at around 44,000 yds. The American battleships, being outranged, continued to close thus presenting the Japanese with the opportunity to ‘cross the T’ at long range. South Dakota, in the lead and seemingly a hard luck ship, was straddled several times and suffered one direct hit from an 18” shell which knocked out one of the forward turrets.

As the US ships reached 35,000 yds, they turned onto a nearly parallel course, closing slowly. At this point, all the battleships were engaged, each picking their targets at will. The older Japanese battleships proved to be susceptible to the US 16” shells and suffered several direct hits causing extensive damage and slowly reducing their firepower as mounts were hit and disabled. Yamato and Musashi proved quite resilient and several hits from 16” shells destroyed secondary guns and started fires but were unable to silence their main batteries. The US battleships were hit multiple times, except for Washington, and were slowly being pounded down.

At this point, the three older Japanese battleships fell behind and out of the battle as did the South Dakota. That left the Yamato and Musashi engaged with Washington, North Carolina, and Indiana. The US had a greater combined rate of fire while the Japanese had heavier firepower. As the battle dragged on, all the ships suffered additional hits and were slowly being worn down but the greater volume of fire from the American ships began to tell. The Japanese broke off the engagement and the battered Americans were quite willing to let them go.

Mutso and Fuso eventually sank, as did the South Dakota. The remaining ships on both sides would be out of the war for several months.

South Dakota Fighting Mutso and Fuso

In the aftermath, the battle was a tactical draw with the Japanese losing two carriers, Akagi and Kaga, plus two older battleships and the US also losing two carriers, Hornet and Wasp, plus the South Dakota. However, strategically, the Japanese failed to stop the American invasion force and Midway was seized thus setting the stage for the eventual recapture of Pearl Harbor. Historians view the Battle of Midway as the turning point of the war.

After Midway, the US war industry began to hit its stride and new Essex class carriers began arriving along with the new Iowa class battleships and replacement aircraft and pilots. Japan was unable to match the industrial output and could not replace their losses as readily. This trend would continue and worsen as the war progressed. The end was inevitable although four more years of bitter fighting still lay ahead.

__________________________________

(1)Naval History and Heritage Command website,

“An Advance Expeditionary Force of large submarines, five of them carrying midget submarines, was sent to scout around Hawaii, dispatch the midgets into Pearl Harbor to attack ships there, and torpedo American warships that might escape to sea.”

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-co...panese-forces-in-the-pearl-harbor-attack.html

(2)National Geographic website, Map of Pearl Harbor facilities: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2018/12/pearl-harbor-maps--atlas-of-WWII/

(3)Navy Matters blog, “Open Post”, 27-Mar-2019, Purple Calico March 27, 2019 at 7:22 AM

(4)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Pearl_Harbor

https://navy-matters.blogspot.com/2019/04/japanese-invasion-of-pearl-harbor.html

All credit belongs to ComNavOps. I copied the post in its entirety for ease of discussion, but please check out the author's blog.

Here’s another ‘what if’ version of history: what if the Japanese had immediately invaded Hawaii after attacking Pearl Harbor? How would the war have progressed from that point? Let’s see.

Note: Credit for this idea goes to blog reader ‘Purple Calico’ who suggested the topic during the recent open post discussion. (3)

The initial premise is that the attack on Pearl Harbor and all the related events happened exactly as history records except that the Japanese fleet contained an invasion force and the Japanese continued on to Pearl Harbor rather than turning away.

To review, the Japanese strike fleet consisted of 6 aircraft carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku) with well over 400 aircraft, protected by 2 battleships, 3 cruisers, and 9 destroyers (all actual). Accompanying the strike were 8 tankers (actual) which would prove crucial in our alter-history by sustaining the fleets while the island was being secured.

In addition, 23 fleet submarines (actual, 4) were assigned to provide containment around Pearl Harbor to prevent any surviving US ships from escaping to open waters (1) and screening for the strike and invasion fleets. A third were assigned to screen the fleet to the east of Oahu, another third capped the Pearl Harbor channel to the south, and the remaining third patrolled the waters to the west of Oahu.

The alter-historical addition to the Japanese strike fleet is an invasion force consisted of an armored division with 10,000 men and 270 tanks plus dozens of artillery and anti-tank guns plus an infantry division of almost 25,000 men supported by several dozen artillery guns, all loaded on dozens of transport vessels.

The attack on Pearl Harbor came from the north with the 1st wave launching around 220 miles north of Pearl Harbor. The strike fleet continued to sail east and launched the 2nd wave from the northeast.

The first two attack waves succeeded in sinking or damaging nearly all the battleships and cruisers and eliminated effective aerial resistance. Of the 402 American aircraft in Hawaii, 188 were destroyed and 159 damaged, 155 of them on the ground (actual).

Note: An outstanding map of Pearl Harbor ships and facilities at the moment of attack can be found on the National Geographic website. (2)

What follows is a descriptive alter-historical summary of events beginning immediately after the 2nd assault wave of Japanese aircraft.

A 3rd wave was launched from east of Oahu and focused on the ten or so destroyers which had been largely untouched in the first two strikes and any remaining aircraft on the ground. By the time the 3rd wave was finished, there were very few undamaged ships in Pearl Harbor.

The strike fleet continued sailing in a clockwise circle around Oahu, escorting the transport vessels. The land assault would be focused on the militarized island of Oahu which contained the Pearl Harbor naval base, Marine barracks, and multiple air fields. The remaining Hawaiian islands did not need to be occupied. This allowed the Japanese to concentrate their resources on a single small island only 20 miles or so across.

With no American air power to worry about, the two Japanese battleships raced ahead of the rest of the invasion and strike fleets and entered the Pearl Harbor channel at dusk. Their mission was to destroy any remaining ships, bombard the facilities that the Japanese didn’t need to occupy and reuse, and to distract from the assault force that began their landings at the same time. There was risk with attempting an evening landing rather than waiting for dawn but it was felt that the risk was worth it to maintain the shock and confusion that the reeling Americans were under.

As it turned out, the Japanese battleships were hugely successful with the Americans firing on their own ships as much as the Japanese did due to the darkness, confusion, and panic. With reports of Japanese troop landings, and the evidence of Japanese ships in the harbor, American troops began firing on their own ground forces as they were totally untrained and unprepared for night combat and had not trained for friendly forces identification. By morning, the Japanese ground forces were well established and by the end of the day on the 8th were in control of the Pearl Harbor facilities.

Japanese Forces Landing on Oahu

The USS Enterprise, returning from delivering Wildcats to Wake Island, was 215 miles west of Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacks began. Several of Enterprise’s SBDs had flown ahead to Pearl and were shot down by friendly fire. Enterprise spent the day of the 7thsearching for the Japanese strike fleet but found nothing since the Japanese fleets were on the opposite side of Oahu. As reports of Japanese invasion forces reached Enterprise, Admiral Halsey headed southeast and began to assemble an aerial strike force. Unfortunately, that brought Enterprise into the teeth of the Japanese submarine screen and a Japanese submarine found her and put three torpedoes into the ship. Over the next several hours, a second Japanese submarine was able to approach and hit Enterprise with two more torpedoes. Her fate was sealed. Enterprise was a blazing wreck and eventually sank during the night of the 8th.

Enterprise Torpedoed and Sinking

Meanwhile, Lexington, which had been on a mission to deliver planes to Midway, found herself caught halfway between Midway and Pearl Harbor and with her escorts low on fuel due to previous refueling difficulties (actual). With Enterprise sunk, the Japanese dispatched four carriers to search for Lexington and, on the 12th, found her, thus setting the stage for the first carrier battle where the opposing ships never saw each other. Both sides launched nearly simultaneous attacks. Lexington, with only a single air group which included over a dozen older Brewster Buffalos, was unable to fight off the Japanese attack and suffered two bomb hits, two torpedoes, and a damaged Japanese plane that dove into the carrier. Lexington’s strike, facing the defensive CAP of four carriers, managed to score two bomb hits on the Kaga which damaged the carrier enough to curtail flight operations but did not sink it. Both sides recovered their strikes but the Japanese, with greater numbers, were able to launch a second, standby, strike before Lexington could effect repairs sufficient to assemble another strike. The second strike finished off the Lexington.

This left Saratoga, which was training her air group in San Diego, as the only US carrier in the Pacific. Yorktown, Hornet, and Ranger and Wasp were training in Norfolk. Ranger was considered unsuited for the Pacific and was destined for Atlantic and European operations. It would be many weeks before Yorktown, Hornet, and Wasp could be moved to the Pacific and the Japanese used that time to secure Pearl Harbor and set it up as their forward base. Japanese army aircraft fighters were ferried to the island along with long range patrol planes and bombers.

One of the major benefits for the Japanese in seizing Pearl Harbor was the presence of the drydocks which they had wisely and carefully avoided damaging in the initial attacks and which were captured largely intact and quickly returned to service. Damaged Japanese ships which might otherwise have had to return to Japan for repair, were able to be serviced locally, at Pearl Harbor, and returned to combat much quicker. This was significant as even the base at Truk lacked significant repair facilities.

Fall of Wake – On 11-Dec-1941, Wake defenders fought off the first Japanese landing attempt, sinking two Japanese destroyers with coastal defense guns and Wildcat aircraft. A second assault initiated shortly after midnight on 23-Dec-1941 succeeded and the island fell later that same day.

Seizure of Tulagi and Port Moresby (Coral Sea) – The Japanese planned to seize Tulagi and Port Moresby in operations that began in April 1942. The Americans were able to intercept and decipher Japanese signals and knew the general location and timing of the operations. Having lost Pearl Harbor, the threat to Australia as a forward base was considered strategically vital and an operation to intercept the Japanese in or around the Coral Sea was initiated. The carrier Yorktown, recently arrived in the Pacific, was patrolling in the area to the west of Australia and Saratoga was dispatched from San Diego to join her and meet the Japanese invasion fleet. The Japanese sent the Carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, and Shoho to screen the invasion forces from the north and a surface force centered around the battleship Yamato approached from the northeast from Pearl Harbor. Despite the efforts of their respective scout aircraft, the two sides stumbled across each other during the night of 6-May with the Yamato group sighting the Yorktown and Saratoga which had joined up the previous day. The Japanese and American destroyer screens made contact and exchanged fire in a wild night battle which the Japanese cruisers and the Yamato quickly jumped into. When word came that a Japanese battleship was part of the attack, the American carriers conducted an impromptu and untrained-for night launch and attack. Despite the darkness and their lack of training, the untrained flyers succeeded in hitting Yamato with one torpedo and a cruiser was hit with two bombs. Unfortunately, in the darkness, confusion, and co-mingling of the ships, the flyers also torpedoed and sank a US destroyer. As dawn approached, and fearing further aerial attacks, the Japanese broke off the attack and steamed away.

Yorktown and Saratoga Night Attack on Yamato

However, with the US carrier force now located, the Japanese carriers launched a heavy dawn attack which caught the US carriers and their exhausted pilots unprepared. Saratoga was heavily damaged by multiple torpedoes and bombs and Yorktown suffered two bomb hits. When the attack ended, Yorktown, whose dawn scouting planes had located the Japanese carriers, was still able to conduct flight operations and launched a counterattack which caught the Japanese carriers refueling and rearming their aircraft. Shoho was sunk and Shokaku was heavily damaged.

After recovering her aircraft, Yorktown broke off the engagement and retired to the southeast and back to San Diego for repairs. Saratoga was taken under tow but the Yamato group, reversing course and returning to the area to mop up, fell upon the carrier and sank it with gunfire.

The Battle of the Coral Sea, as it came to be known, was a tactical draw but because the US was unable to stop the Japanese invasion fleet which still had sizable carrier and surface forces in the area to provide protection, the Japanese were able to complete the seizure of Port Moresby which was then used as a staging area to threaten Australia directly.

With the loss of Saratoga, only the Hornet, Wasp, and damaged Yorktown remained from the pre-war US carrier force.

The Japanese then seized Midway, costing the US the valuable PBY Catalina patrol and scouting base. Despite having knowledge of the Japanese intentions via signals analysis, the US simply didn’t have the naval strength to contest the Japanese invasion.

The US was now forced to operate from Australia, the Aleutians, and San Diego. None of these options was desirable although Australia was, at least, near the action due to the Japanese seizures. US efforts for the next several months centered on reinforcing Australia and beefing up its defenses. If Australia fell, the US would be effectively ejected from the Pacific theatre.

Taking a cue from the Germans, the Japanese began conducting aggressive Australian convoy interdiction using submarines based out of Pearl Harbor. The Battle of the Pacific, mirroring the Battle of the Atlantic, became a logistic supply contest with the US attempting to reinforce Australia and the Japanese attempting to cut the supply line.

The Japanese, having essentially secured the Pacific now focused on a holding strategy in an attempt to force the US into a negotiated peace. The Japanese believed that the US, already occupied with the war in Europe, would grow weary of fighting a difficult war in the Pacific and lacked the stomach for the casualties such an endeavor would entail.

To that end, in late 1942 the Japanese dispatched a strike force of carriers and battleships to the west coast of the US to conduct bombardment raids which, it was hoped, would further discourage a demoralized populace and force the US to negotiate. The strike force arrived off the coast of Washington and began moving south, bombarding cities and targets of opportunity as they went. The intent was to inflict some casualties and instill fear in the populace rather than achieve any specific military success. After 24 hours of nearly continuous bombardment, the group turned away and retired to avoid the inevitable surge of US naval forces to the area from San Francisco and San Diego.

Japanese Battleship Bombarding Washington Coast

While the operation was executed flawlessly the reaction of the American people was a surge of anger, defiance, and cries for revenge and retaliation. As a result of the raid, US determination to defeat Japan was greater than ever, much to the disbelief of the Japanese strategists.

There was little doubt that the US needed to recapture Pearl Harbor to support the war with Japan. However, by this time, Japan had had a year to fortify the base and seizing it by a direct assault with the closest support being the US west coast was not immediately feasible. Instead, US military strategists opted to seize Midway atoll first and then use Midway to screen and support a subsequent assault against Pearl Harbor. An invasion force consisting of Maj. Gen. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division and supported by the carriers Yorktown, Hornet, Wasp, and the newly arrived Essex along with RAdm. Willis ‘Ching’ Lee’s battleship group of North Carolina, Washington, Indiana, and South Dakota was assembled in the Aleutians at Dutch Harbor and sailed for Midway in May 1943.

As the force approached Midway from the north, the carriers broke off and circled to the east to take a position to the southeast of Midway, somewhat between it and Pearl Harbor. As expected, the battleships and troop transports were spotted by long range patrol planes from Midway. The Japanese surged four carriers and their escorts, including the battleships Yamato, the newly arrived Musashi, and the older battleships Nagato, Mutsu, and Fuso from Pearl Harbor to intercept the American force.

The US transport fleet hung back while the battleship group and its escorts took the lead. As the US fleet approached Midway, the Japanese launched two aerial strikes of high level bombers from Midway. The concentrated anti-aircraft fire of the US battleships and escorts, combined with the inherent inaccuracy of high level bombing resulted in only two hits: one bomb hit the South Dakota resulting in only minor damage and a more serious hit on a cruiser which was forced to retire northward.

Having yet to spot any US carriers, the Japanese saw the chance to engage the US battleships in the long-desired battle line confrontation. The Japanese battleships sprinted ahead to meet the US battleships.

Japanese Battle Line Steaming To Meet US Battleships

Shortly after, scout planes from the Japanese and US carrier forces located each other, roughly simultaneously and both sides launched strikes at the other’s carriers. Each realized that the carriers were the priority targets and that their respective battleship forces would have to take care of themselves without the benefit of air cover.

The Japanese strike aircraft reached the American carriers first and managed to penetrate the carriers CAP and escort screen to put two torpedoes into Hornet and one into Wasp. Essex and Wasp were each hit by two bombs. The US strike failed to achieve any torpedo hits but put three bombs into Akagi, and two into Soryu. At the end of the exchange, Wasp was left ablaze and drifting while Essex worked frantically to control internal fires and patch her flight deck. Hornet was slowed due to flooding but otherwise operational. On the Japanese side, Japanese damage control measures proved to be less effective than US efforts and Akagi was left a wreck and Soryu was badly damaged but working to regain operational ability.

A brief pause ensued while both sides worked on damage control and refueled and rearmed for a follow up strike.

Meanwhile, to the northwest, the US battleships, using their SOC Seagull and OS2U Kingfisher scout planes, were aware of the approaching Japanese battleship group and moved to meet them.

While the two forces sailed towards each other, the carriers launched their second strikes. This time, the US carriers were able to turn their strike groups around a bit faster than the Japanese and struck first. The pilots bypassed the blazing Akagi and concentrated on Kaga and Hiryu, managing to put a single torpedo into Kaga along with three bombs. Hiryu suffered one bomb hit and two near misses. The Japanese strike found Hornet and Essex and put three torpedoes into Hornet along with two bombs and Essex was hit by another bomb and a torpedo. Both strikes returned to their carriers and both carrier groups broke off from the engagement, too damaged to continue.

By this time, the approaching battleship groups were entering into range of each other. This turned into the classic battle line engagement with the two groups turning to face each other. Thanks to the Yamato and Musashi the Japanese battleships held an initial range advantage and opened fire at around 44,000 yds. The American battleships, being outranged, continued to close thus presenting the Japanese with the opportunity to ‘cross the T’ at long range. South Dakota, in the lead and seemingly a hard luck ship, was straddled several times and suffered one direct hit from an 18” shell which knocked out one of the forward turrets.

As the US ships reached 35,000 yds, they turned onto a nearly parallel course, closing slowly. At this point, all the battleships were engaged, each picking their targets at will. The older Japanese battleships proved to be susceptible to the US 16” shells and suffered several direct hits causing extensive damage and slowly reducing their firepower as mounts were hit and disabled. Yamato and Musashi proved quite resilient and several hits from 16” shells destroyed secondary guns and started fires but were unable to silence their main batteries. The US battleships were hit multiple times, except for Washington, and were slowly being pounded down.

At this point, the three older Japanese battleships fell behind and out of the battle as did the South Dakota. That left the Yamato and Musashi engaged with Washington, North Carolina, and Indiana. The US had a greater combined rate of fire while the Japanese had heavier firepower. As the battle dragged on, all the ships suffered additional hits and were slowly being worn down but the greater volume of fire from the American ships began to tell. The Japanese broke off the engagement and the battered Americans were quite willing to let them go.

Mutso and Fuso eventually sank, as did the South Dakota. The remaining ships on both sides would be out of the war for several months.

South Dakota Fighting Mutso and Fuso

In the aftermath, the battle was a tactical draw with the Japanese losing two carriers, Akagi and Kaga, plus two older battleships and the US also losing two carriers, Hornet and Wasp, plus the South Dakota. However, strategically, the Japanese failed to stop the American invasion force and Midway was seized thus setting the stage for the eventual recapture of Pearl Harbor. Historians view the Battle of Midway as the turning point of the war.

After Midway, the US war industry began to hit its stride and new Essex class carriers began arriving along with the new Iowa class battleships and replacement aircraft and pilots. Japan was unable to match the industrial output and could not replace their losses as readily. This trend would continue and worsen as the war progressed. The end was inevitable although four more years of bitter fighting still lay ahead.

__________________________________

(1)Naval History and Heritage Command website,

“An Advance Expeditionary Force of large submarines, five of them carrying midget submarines, was sent to scout around Hawaii, dispatch the midgets into Pearl Harbor to attack ships there, and torpedo American warships that might escape to sea.”

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-co...panese-forces-in-the-pearl-harbor-attack.html

(2)National Geographic website, Map of Pearl Harbor facilities: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2018/12/pearl-harbor-maps--atlas-of-WWII/

(3)Navy Matters blog, “Open Post”, 27-Mar-2019, Purple Calico March 27, 2019 at 7:22 AM

(4)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Pearl_Harbor